A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

BY Ar. Nayeem Bin Abedin and Ar. Shahriar Mahmud

June 05, 2025

It’s 2013. A young college student from Jatrabari is stuck in a long, sweaty traffic jam on his way to 9 AM class. The early heat is unbearable, and his white shirt is already covered in a layer of dust. He sneezes, his eyes sting from the pollution, but he has no choice but to keep the window open. The construction of the flyover is progressing, and it’s all around him– massive cranes and piles of concrete blocking the lanes and adding to the chaos.

Fast-forward to 2025. The boy is now a faculty member guiding his students on a study tour to Ashulia. The Dhaka-Ashulia expressway project is progressing in full swing which makes him feel a sense of awe.

But soon, he finds himself stuck in yet another mile-long traffic jam. Due to the construction, the road has been narrowed to a single lane, and large cranes block the only path forward. The heat and dust flow in from the open window, and in an instant, he’s transported back to his college days. Nostalgia sets in, but with it comes a grim realization: Dhaka hasn’t changed much.

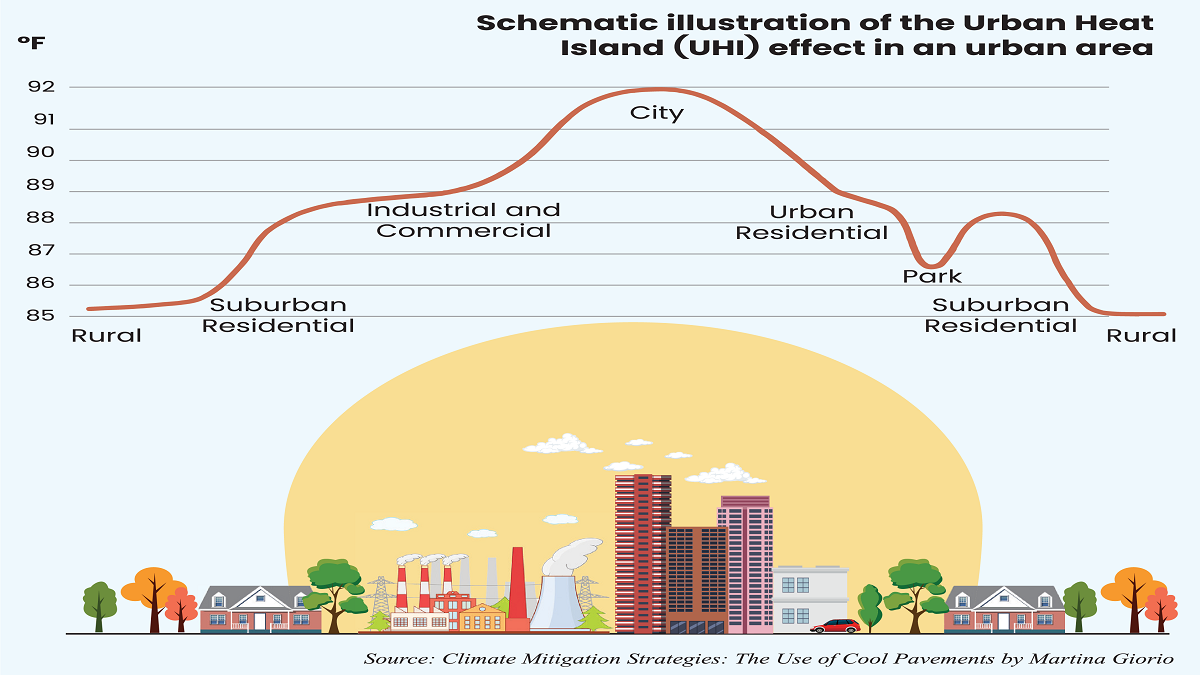

If anything, it has taken a turn for the worse. Every year, the city’s streets feel hotter, buildings burn up like ovens, and the air smokes. Global warming and climate change are not the only criminal duos here; it’s also from the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, which caused Dhaka to get significantly warmer than its surrounding neighbors.

Dhaka is the fourth most densely populated city globally, with over 22 million people. A massive rise in population resulted in the removal of natural land cover over a vast area for urban expansion. The increased build-up areas and reduced natural land cover raised the temperature.

Though the global impacts of urbanization and industrialization are severe, the regional effects are even more severe in the areas where various industries take birth or complex construction materials are used unprofessionally. This phenomenon severely affects the natural environment and ecology.

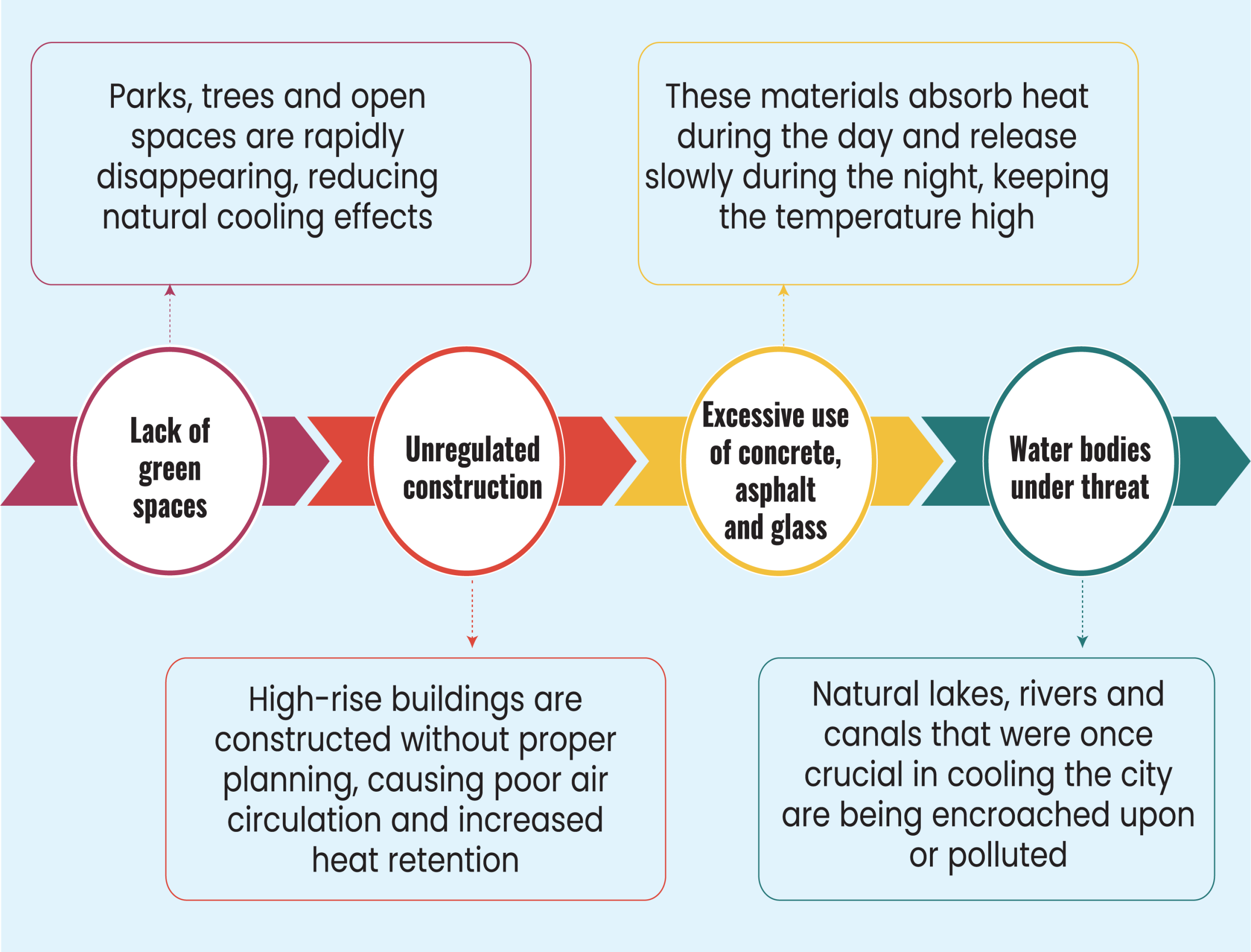

Green spaces—once nature’s air conditioners—are rapidly becoming extinct, replaced by high-rises and shopping malls. Buildings are packed tightly together, blocking natural airflow and creating a massacre for claustrophobes. Asphalt roads and glass structures absorb and re-radiate heat, turning the city into a concrete-fire oven.

On a scorching summer day, temperatures in Dhaka’s heart can be 3 to 4 degrees Celsius higher than in its outskirts. This is uncomfortable and unhealthy, increasing energy consumption and reducing overall quality of life.

Asphalt pavement generally produces little noise, is relatively low-cost compared to other materials, and is relatively easy to repair. At first glance, it seems like the perfect fix—cheap, quiet, and easy to repair. But like a budget umbrella in a monsoon, it doesn’t hold up for long and isn’t exactly eco-friendly either. Asphalt is known to be significantly less long-lasting than its alternatives and is not the best for the environment either.

Concrete is another popular material choice for roadways. There are two essential kinds of concrete street surfaces: jointed reinforced concrete pavement (JRCP) and continuously reinforced concrete pavement (CRCP).

Concrete lasts longer than asphalt, is appreciably stronger built and is quite highly priced to lay. The color of the pavement surfaces is open to choice, and it affects the temperatures within the city.

The effect of color is understandable because if a surface is dark, it means it absorbs the visible light. This warms the surface, eventually warming the air. The most practical means of mitigating this urban heat island (UHI) is to make urban surfaces brighter, which means they are more reflective of the sunlight.

The thermal performance of a pavement is defined as the change in its temperature (most often surface temperature) over time as influenced by properties of the paving materials such as albedo (the fraction of light that a surface reflects), thermal emittance, thermal conductivity, specific heat, and surface convection, and ambient environmental conditions (sunlight, wind, air temperature).

The use of glass facades in commercial buildings is increasing principally for two reasons. The first is to ensure a clear view of the outdoors from individual working stations, and the second is probably to provide sufficient daylight. Another aspect is that they trap a significant part of the incoming sun, which can be advantageous during the cold.

Also, industrial advancements have made the manufacture and installation of glass curtain walls and other types of glass relatively easy. Architects often use such facades for aesthetic purposes. Since commercial buildings principally use glass facades, architects need to have a clear view regarding the properties of the type of glass.

The properties of glass that indicate heat penetration are- visible light transmittance, U-Value, reflectance, solar heat gain coefficient and shading coefficient. These properties of glass either control the amount of heat entering the facade, work as an insulator or reflect a certain amount of light incident upon the glass. So, the value of these properties indicates the glass’s performance in terms of heat penetration.

The loss of green spaces and increased heat-retaining surfaces like concrete and asphalt have created an urban heat island effect in Dhaka. Urban expansion and dense settlements increased the average temperature in some areas of Dhaka city by nearly 3/4 degree Celsius compared to that at its boundary. The ongoing construction preparations make the realistic rise in temperature unbearable.

Even though infrastructure projects like flyovers, bus rapid transit, and motorways are expected to reduce traffic, they come at a high environmental cost and contribute to the city of Dhaka’s already thriving Housing construction industry. The dust from construction sites, vehicle emissions, and narrow roads all contribute to the deteriorating air quality.

Cities like New Delhi and Dhaka consistently experience air quality levels that exceed hazardous thresholds, with AQI values frequently surpassing 500. This level of pollution poses a significant threat to public health, particularly among vulnerable groups such as children, the elderly, and those with preexisting conditions.

But does Dhaka have to suffer this fate? The answer is a simple no. The solution lies in thoughtful and efficient urban planning. With growing awareness about the urban heat island effect and air pollution, Dhaka has started to shift towards more sustainable urban planning. Green infrastructure—such as parks, tree-lined streets, and green rooftops—has started to become a priority.

The city needs a comprehensive and sustainable approach to urban planning. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) reported that introducing green spaces and reflective surfaces can reduce urban temperatures by up to 3°C, improving both the environment and public health.

Dhaka’s future depends on how it embraces sustainable urban development. The heat may be rising, but so can our standards for smarter urban planning. For now, though, it’s clear that Dhaka still has a long way to go.

Ar. Nayeem Bin Abedin and Ar. Shahriar Mahmud are both architect, researcher and academician. They are also associate members of the Institutes of Architects Bangladesh (AMIAB).

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like