From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

August 08, 2025

Day after day, thick smog gripped the cities, making the sight of a clear blue sky a distant daydream. School closures and emergency guidelines became commonplace, with severe implications for not taking preventive measures when going outside.

Despite economic well-being and a rise in purchasing power, people knew that nothing is worth the price of clean air. Such was the scenario in China in 2013, from which the country has overcome.

What worked for China has implications for countries trying to balance economic growth and environmental conservation.

How bad was China’s air?

Common causes of air pollution include motor vehicles, industrial operations, household combustion devices, and forest fires. Particulate matter, carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide are among the pollutants that pose the greatest threat to human health.

Both indoor and outdoor air pollution contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality by causing respiratory and other illnesses.

More people have been lifted out of poverty in China than in any other nation. However, that rapid economic growth, specifically due to its reliance on fossil fuels, did not come without a cost.

The Global Burden of Disease study estimates that in 2019, ambient (atmospheric particulate matter) PM2.5 pollution resulted in approximately 1.4 million premature deaths in China. It has proven to be expensive for the country, as crop failures brought on by pollution cost the economy $37 billion annually.

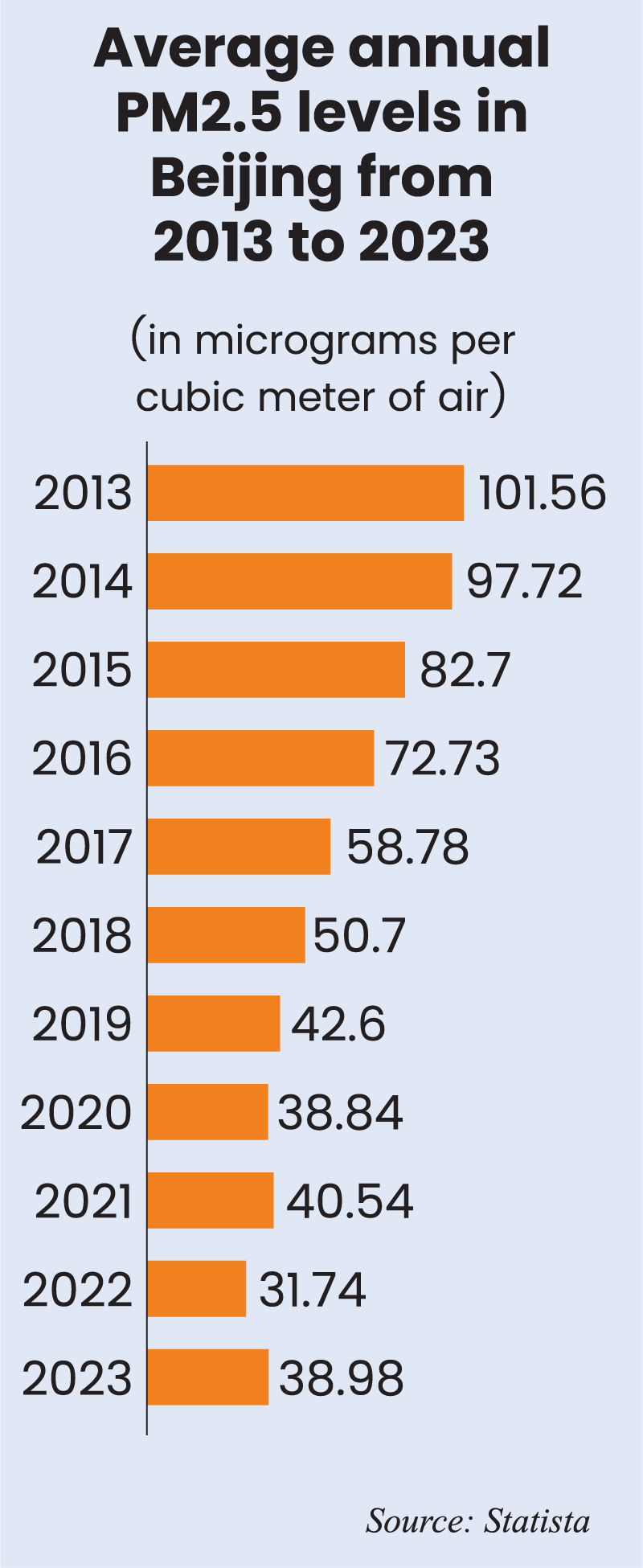

The air quality had deteriorated so badly in 2013 that the PM2.5 level had risen to 101.56 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m³) of air, while the recommended level is 10 µg/m³.

The deteriorating condition, with its massive health and well-being implications, was being termed an ‘airpocalypse.’

China began working to improve the air quality in major cities after this led to a widespread outburst of rage and discontent among the populace.

Policies to rebound

China’s most significant environmental policy was the Air Pollution Action Plan, which was published in September 2013.

Between 2013 and 2017, it significantly improved the country’s air quality, lowering PM2.5 levels by 15% in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) and 33% in Beijing. This brought Beijing’s PM2.5 levels down from 89.5 µg/m³ to 60 µg/m³.

However, despite these efforts, none of the cities were able to achieve the 10 µg/m³ annual average PM2.5 threshold recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Only 107 of China’s 338 cities at the prefectural level or higher had achieved the WHO’s interim criteria of 35 µg/m³ by the end of 2017.

China then unveiled its Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the Blue Sky War in 2018, marking the second phase of its fight against air pollution.

This plan was significant for several reasons. The new three-year Action Plan was applicable to all Chinese cities, whereas the 2013 Action Plan only established PM2.5 level targets for the Pearl and Yangtze Deltas and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei city clusters.

Up to 231 cities that have not yet achieved the government-mandated average of 35µg/m³ must reduce their PM2.5 levels by at least 18% compared to a baseline set in 2015.

Ground-level ozone, a highly irritating gas produced by the reaction of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with nitrogen oxides generated from automobiles, was a major contaminant that made the air lethal in many places and was not addressed in the prior plan.

Ozone in the upper atmosphere shields the planet from solar radiation, but it is highly harmful in the troposphere and can lead to respiratory tract illnesses and asthma among locals.

With the addition of targets for both VOCs and nitrogen oxides—emissions reductions of 10% and 15%, respectively, by 2020—the new action plan placed a greater emphasis on ozone pollution.

Visible progress

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which originated in Wuhan, Hubei Province, and led to the country implementing the strictest lockdowns in history, the quality improved, and greenhouse gas emissions decreased as a result of a decline in economic and industrial activity.

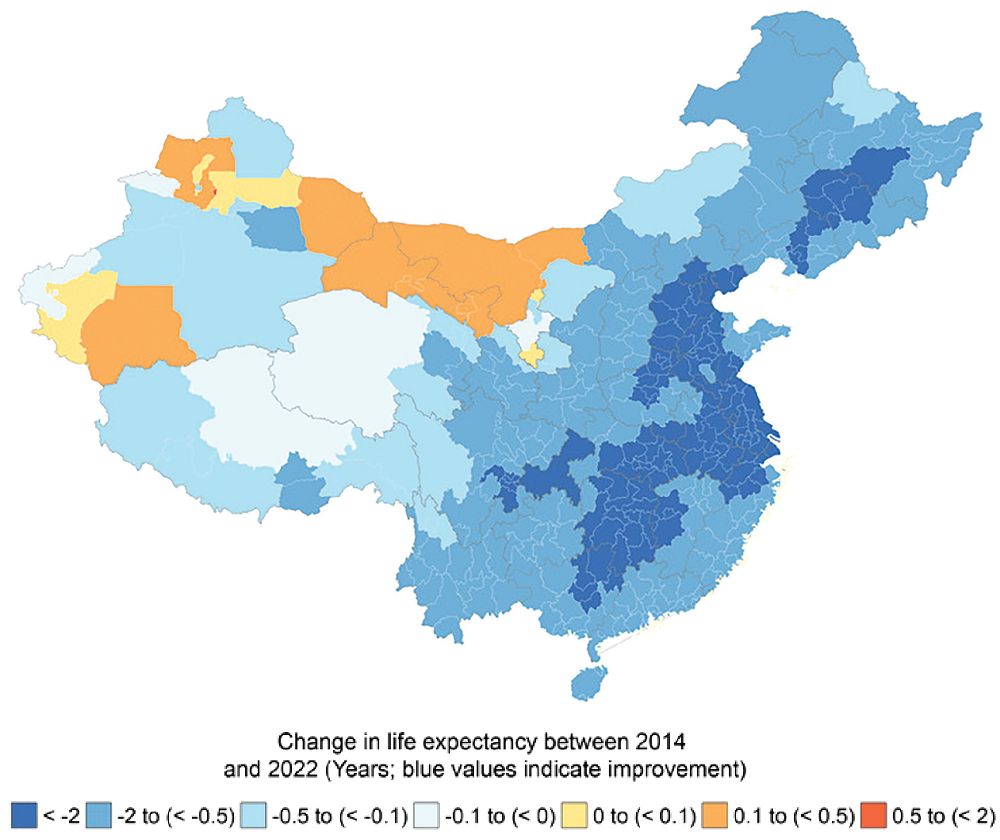

China’s fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) has been decreasing since the country launched its anti-pollution campaign. This decline has continued through 2022, with pollution levels down by 41 percent compared to 2013, according to the Air Quality Life Index, 2024.

The official decision, made in 2014, has led to a significant decline in pollution levels compared to historical data (Air Quality Life Index, 2024).

(Below the page) *PRD, which stands for Pearl River Delta, encompasses the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau as well as the dense network of cities that span nine prefectures of the province of Guangdong: Dongguan, Foshan, Guangzhou, Huizhou, Jiangmen, Shenzhen, Zhaoqing, Zhongshan, and Zhuhai. The Yangtze River Delta, also known as the YRD, comprises Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai. Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei is referred to as BTH.

Bangladesh faces similar struggles

The severity of air pollution is a common phenomenon worldwide, and the situation in Bangladesh is particularly dire. During winter months, smog can be seen with the naked eye.

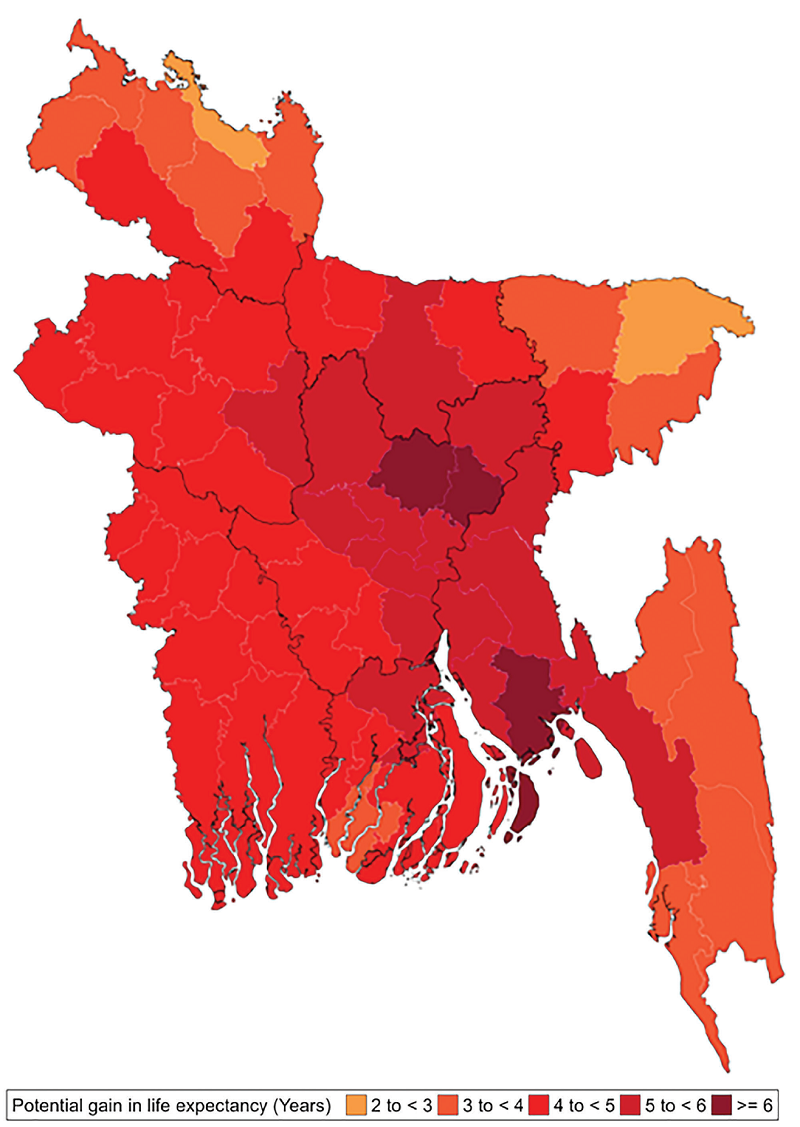

96.8% of Bangladesh’s population lives in places that don’t satisfy the nation’s own national requirement of 35 µg/m³, and all 166.4 million people reside in locations where the yearly average particle pollution level exceeds both the WHO guideline and the standard.

Particulate pollution is 6.7 times higher than the WHO recommendation, even in Sylhet’s least contaminated district.

75.9 million people, or 45.6% of Bangladesh’s total population, live in some of the most polluted areas of the nation, which are dispersed throughout Dhaka and Chattogram. They are expected to lose an average of 5.4 years of life expectancy in comparison to the WHO recommendation.

If Bangladesh could lower particulate pollution to WHO standards, Bangladesh’s life expectancy would increase by 5.6 years. Life expectancy in Dhaka and Chattogram would rise by 2.6 and 2.3 years, respectively, even if these cities could reach Bangladesh’s national average air pollution level.

Taking lessons from the Chinese success case

Despite the differences in the economic and political structures of China and other countries, such as Bangladesh, China’s success has several implications for their ongoing struggle against pollution.

The most effective measure that worked for China was identifying the pollution hotspots. The importance of data is often overlooked in policy decisions, further exacerbating the challenges associated with interventions.

In China, a state-of-the-art integrated air quality monitoring network was built in 2016, which led to the employment of high-grade technologies such as HD satellites, remote sensing, and laser radar.

With over 1,000 sensors spread throughout the city, network technologies that track PM2.5 levels helped locate the regions with the highest pollution levels.

One of the biggest obstacles to understanding and analyzing the condition and impacts of dry powder inhaler (DPI) in Bangladesh is obtaining accurate and current data.

Although considerable effort has been invested in data infrastructure, several discrepancies exist in the way data is managed and stored by both government and non-governmental organizations. There are no centralized data repositories to accurately reflect current time data.

China had effectively decreased the proportion of coal in its energy mix before the pandemic, from 67.4% in 2013 to 57.7% in 2019.

In the most polluting areas, such as the Pearl and Yangtze Deltas and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei metropolitan clusters, the government outlawed the construction of new coal-fired power plants and closed many existing ones. The nation closed coal mines and decreased its capacity to produce iron and steel.

This is at the core of the debate on state control and the reign of the free market. While in authoritarian China, it was simple to control production, in democracies, public support has to be garnered to regulate polluting businesses for the greater good.

On the other hand, having policies on paper, as is often the case in most developing countries, is not enough. Policies must be implemented to ensure that the existing regulations effectively benefit the broader population.

For the first time in its history, China’s wind and solar power generation capacity surpassed that of fossil fuel-based thermal power, reaching 1,482 gigawatts by the end of March, per a Reuters report.

China has initiated a rapid growth program for renewable electricity, with new installations reaching record levels in recent years, while being one of the few nations still commissioning new carbon-intensive coal-fired power plants.

According to a report published by the ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability, the expansion of urban rail was one of the leading causes of the significant change.

A sustainable mobility paradigm replaced the nation’s automobile-heavy transportation system. Big cities like Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Shanghai began implementing all-electric bus fleets and limiting the number of cars on the road.

The subsidization of electric cars should be viewed positively from the perspective of a free market economy, particularly in cases of market failure. Essentially, the value to society is not fully disclosed by individual willingness to pay, as this is a manifestation of the tragedy of the commons, which is something as crucial as air in this case.

Additionally, China has planted approximately 35 billion trees in 12 provinces and implemented vigorous afforestation and reforestation initiatives, such as the Great Green Wall.

With more than $100 billion invested in these programs, China’s forestry spending per hectare surpassed that of the US and Europe and exceeded the global average by a factor of three.

Effective data monitoring, strong implementation of policies, and coordinated government efforts have brought back clear blue skies in major Chinese cities, a rare phenomenon only a few years back.

This shows the feasibility of reversing course to restore ecological balance, as well as the slippery slope of wrong policy decisions.

A country like ours, whose priorities hinge on economic growth, should acknowledge the importance of balancing out the environmental impact and enact trajectories accordingly.

Lubaba Mahjabin Prima is a research assistant at the South Asian Network on Economic Modelling (SANEM)

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like