Behind dairy’s unrealized potential

May 11, 2025

Not too long ago, the rhythmic clinking of metal milk containers signaled the arrival of the Goalas—traditional milk collectors who supplied fresh dairy to Bangladeshi households. Families would gather around, eager to buy fresh milk delivered straight to their doorsteps.

But today, that familiar sight has largely disappeared from urban areas, replaced by neatly packaged milk cartons in supermarkets.

Over the past few decades, Bangladesh’s dairy industry has undergone a significant transformation. The rise of industrial milk processors has replaced fragmented supply chains with large-scale operations that prioritize hygiene, efficiency, and quality assurance.

A new era for milk processing

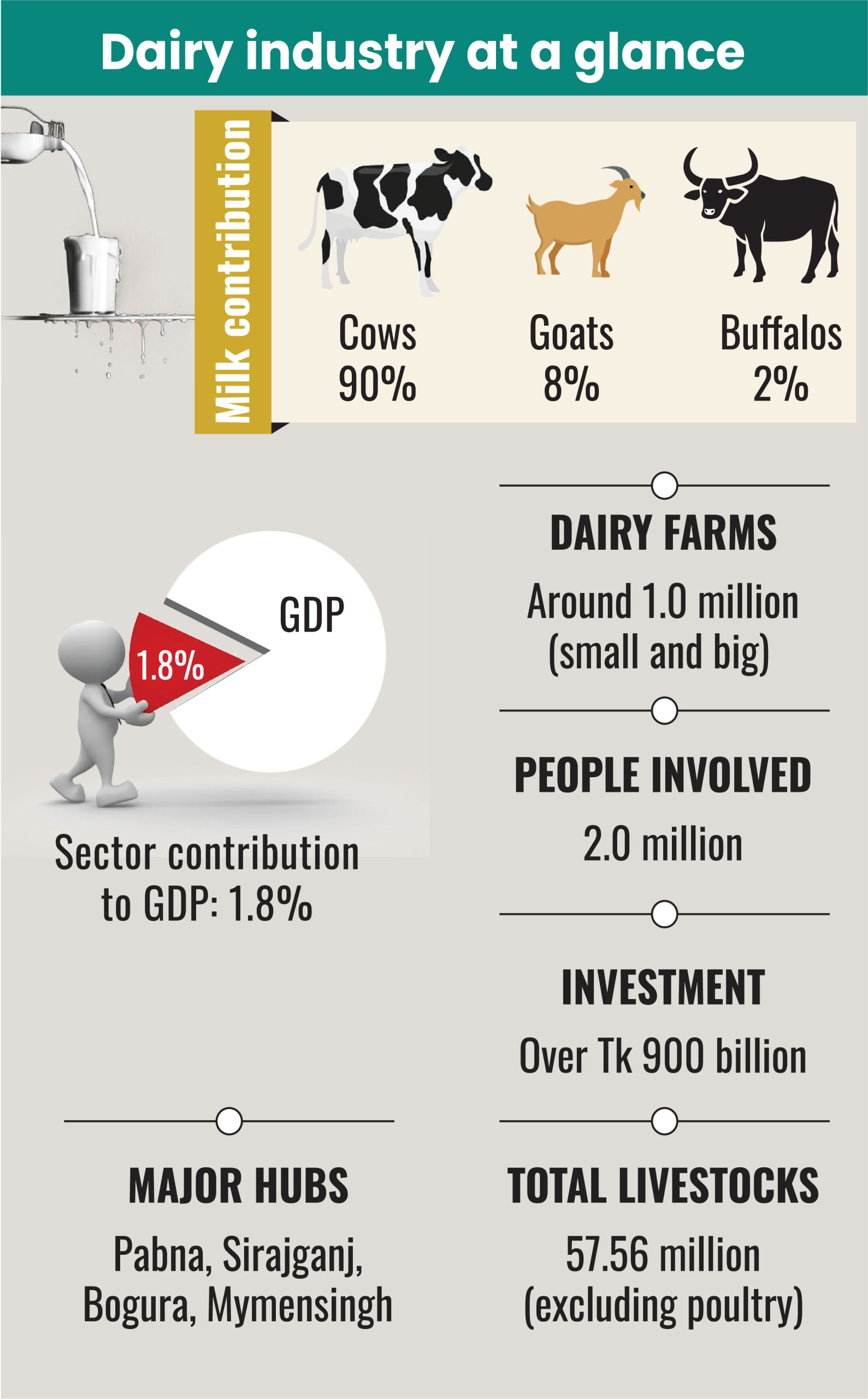

Gone are the days when fresh milk from local cows was the primary choice. Today, more than half a dozen milk processors handle nearly 10 lakh liters of fresh milk every day—more than double the amount they processed just a decade ago. The evolving consumption habits of urban and semi-urban populations are driving this rapid expansion.

The country witnessed some initiatives from various stakeholders, including government, conglomerates, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), to take steps to support the dairy industry.

“The demand for milk and dairy products is rising due to growing awareness of nutrition and higher consumer income,” said Kamruzzaman Kamal, marketing director of PRAN-RFL.

As one of Bangladesh’s largest dairy processors, PRAN entered the dairy business in 2003 and has built an extensive milk collection network. It works with over 50,000 farmers and introduces value-added products such as flavored milk and cheese.

However, due to domestic production shortfalls, Bangladesh remains heavily reliant on milk powder imports, he noted.

Alongside Pran, as a cooperative model, Milk Vita–Bangladesh’s largest dairy cooperative, provides a model for how organized efforts can transform the sector.

Founded in 1973, Milk Vita operates through a cooperative system in which thousands of smallholder farmers supply milk to centralized processing centers. It offers veterinary services, quality feed, and training programs, improving productivity and income levels. It invests in cold chain infrastructure to ensure fresh milk reaches consumers nationwide.

Private sector and NGO participation have further strengthened the industry. Aarong Dairy, a BRAC initiative, has expanded its product line to include pasteurized milk, yogurt, ghee, butter, and cheeses, catering to evolving consumer preferences.

Similarly, Farm Fresh, a brand of Akij Food & Beverage Limited, has gained recognition for offering a variety of dairy products that appeal to health-conscious consumers.

Challenges impeding industry growth

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Asia is the world’s leading milk-producing region, with significant contributions from Pakistan, India, Kazakhstan, China, Uzbekistan, and Japan.

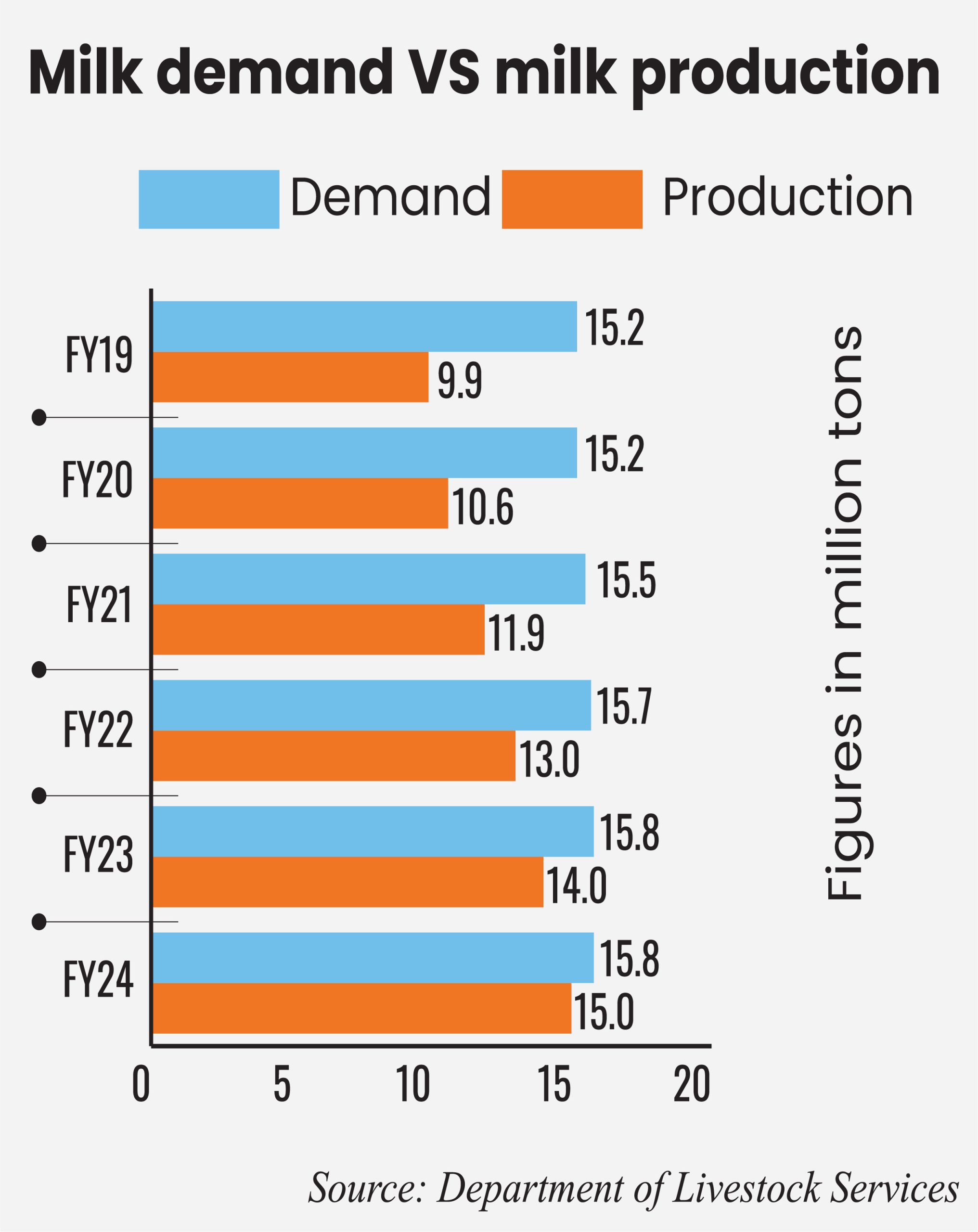

Despite this progress, Bangladesh remains one of the lowest milk-producing countries in Asia. Bangladesh’s dairy sector still struggles with a production shortfall that forces reliance on imports from Australia, New Zealand, and Europe. Per capita milk consumption remains low compared to global standards.

According to the Department of Livestock Services, Bangladesh produced 150.44 lakh tonnes of milk in the 2023-24 fiscal year, falling short of the national demand of 234.45 lakh tonnes.

According to Bangladesh Bank, in the July-December period of the current fiscal year, Bangladesh imported milk and cream at a cost of $188 million, compared to $194.4 million in the same period a year before.

The country imported milk powder and cream at a cost of $395 million or Tk 47.87 billion in the 2023-24 fiscal year, per BB data. This heavy reliance on imports strains foreign exchange reserves and raises concerns about long-term food security and self-sufficiency in the dairy sector.

Despite the huge demand and growth potential, several challenges in the ecosystem impede the industry’s advancement.

One of the biggest challenges is the absence of a formal milk certification authority, which raises concerns about quality control and food safety.

Small-scale farmers, who dominate the sector, often lack access to proper veterinary care, high-quality feed, and efficient distribution channels. Without structured investment in cold storage and processing infrastructure, a significant portion of raw milk goes to waste.

PRAN’s Mr. Kamal attributed this to the fact that many people do not view dairy farming as a viable profession.

“There are huge possibilities in the dairy industry, but it could not flourish like the fisheries industry due to the lack of government attention,” he said.

Lack of quality products

Small-scale farmers and market intermediaries dominate the informal segment of the industry, so quality control processes are apparently non-existent. As farmers do not get fair prices for their produce, they are often tempted to adulterate milk and increase quantity to cover their costs.

A study conducted in the Barishal district found that 100 percent of the samples collected were adulterated with water. Other adulterants present in the samples were cane sugar (26 percent), milk powder (14 percent), and starch (12 percent).

According to industry people, the major obstacles to the industry’s growth are a scarcity of grazing fields for dairy farms, a shortage of high-yielding and quality semen for artificial insemination, the high cost of feed, inadequate treatment facilities for cattle, and a lack of knowledge of dairy farming.

Leaders of the Bangladesh Dairy Farmers Association (BDFA) said that dairy was an emerging sector that could not grow unless a higher tariff was imposed to discourage the import of milk powder.

On the other hand, a lower tax is imposed on milk powder, considering it is baby food, which makes local milk less competitive in the market. However, the officials said a good chunk of imported milk powder is being used for other forms of consumption instead of baby food.

“Definitely, our local farms are highly affected now. The rational tariff can be a good option to grow the local industry,” said Wasif Ahmed Salam, joint secretary of the BDFA.

Besides, Wasif also blamed domestic inflation for their suffering.

“The price of dairy feed has increased way too much, more than two times in the last few years, but our selling price has not increased at that rate,” he said.

“We are facing a loss there since the cost of food is 70% of the total cost per cattle. And other costs like electricity and labor have also increased since inflation,” he added.

Another major challenge is the limited access to veterinary services and modern farming techniques. Many dairy farmers lack knowledge about animal health, nutrition, and breeding, leading to low milk yields and poor-quality products. This affects both the economic sustainability of small farmers and the competitiveness of the dairy industry on a global scale. High feed costs and the lack of subsidies or government support for dairy farmers further undermine their profitability.

“A lack of modern cold storage facilities leads to spoilage and reduces milk quality, particularly in rural areas where dairy farming is prevalent,” said Wasif.

Additionally, the fragmented nature of the dairy supply chain—comprising small-scale farmers—makes it difficult to establish consistent quality control and efficient logistics. This, he explained, contributes to high wastage rates and price volatility.

A spokesperson from one of the members of the Bangladesh Agro-Processing Association (BAPA) blamed the ‘foreign conspiracy’ and governmental non-cooperation.

“Some foreign brands are relentlessly working on it. Sometimes they try to advocate against hiking tariffs on imports as infant food items,” he said, seeking anonymity.

BAPA has criticized the National Board of Revenue’s recent move to hike value-added tax (VAT) on nearly 100 goods and services, including some dairy products. “It may hamper the agro-industry,” they said in a press briefing.

Jahangir Alam Khan, an economist and former vice-chancellor of the University of Global Village (UGV), Barishal, thinks despite having a strong agricultural base and a large dairy farming population, Bangladesh’s dairy industry faces significant barriers that prevent it from becoming a global player.

“There are some key challenges including outdated farming practices, lower production amid higher cost, lack of modern infrastructure, and insufficient cold storage and processing facilities.”

“Compared to Australia and New Zealand, the per unit milk production cost is higher in Bangladesh,” said Mr. Khan, who is the former director general of the Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute (BLRI).

“Truly, we need to increase milk production so that the per unit production cost can be reduced,” he added.

He suggested that a comprehensive overhaul is needed, including the adoption of modern farming techniques, improved infrastructure, and greater investment in research to increase milk production.

“It should be implemented realistically instead of keeping limited in papers.”

Mr. Khan also highlighted the real statistics about the per capita consumption and availability. There is a shortage of feed availability, higher cost of feed, skilled labor, and limited veterinary services, all of which impact productivity and herd health.

“Ensuring the door-to-door health services are needed,” he added.

Milk is a perishable item, and the weak supply chain infrastructure hampers its movement, making it difficult to meet both local and international standards.

Not only the private sector, according to Mr. Khan, the government can also help to install infrastructural development to process raw milk and produce diversified products.

Amul: An unmatched success story in dairy

India’s Amul is a cooperative that transformed India into the world’s largest milk producer. Its efforts in ensuring fair pricing, leveraging technology, and developing a diverse range of products are illustrious.

Amul has a significant impact on India’s economy, dairy industry, and society. It made the ‘White Revolution’ possible, making India the world’s largest milk producer. Its cooperative model benefits over 3.6 million farmers, ensuring fair prices and stable incomes, especially empowering rural women.

Amul also boosts employment, contributes significantly to India’s agricultural GDP, and makes dairy products affordable. Its ‘Amul Girl’ advertising is iconic culturally and globally, and it strengthens India’s dairy exports.

Our way forward

The government should prioritize establishing a milk quality certification authority to standardize production and boost consumer confidence.

Offering financial incentives, such as tax breaks and subsidies, would encourage modernization, while investments in cold storage and processing infrastructure could improve efficiency.

Allocating funds for research and development would enhance productivity, and training programs for farmers on modern techniques would empower the sector. Strengthening cooperative models like Milk Vita and Amul can ensure fair pricing and market stability, benefiting small-scale farmers.

Export policies, public awareness campaigns for certified dairy products, and affordable financing to support small farmers should be the focus. Ensuring better infrastructure, financing, and training could drive sustainable growth in the sector.

With well-thought strategies in place, the industry can become self-sufficient and export-oriented while ensuring the country’s food security and nutrition.

Md Asaduz Zaman is a journalist, specializing in Bangladesh’s economy, environment, and agriculture sectors.

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like