Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

August 09, 2025

The joke about the barely legible handwriting on doctors’ notes is probably a century old. Even though technological innovations have improved many things in our lives, medical prescriptions in Bangladesh have largely remained unreadable.

Patients still deal with stacks of paperwork while visiting care providers; information gets misread during care providing, and there is no easy way to pool all these healthcare records nationally to drive public health policy discussions.

There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to electronic health records (EHR). There are many standards and guidelines from which we can adopt some to cater to Bangladesh’s needs.

What is EHR?

An Electronic Health Record (EHR) is a digitally maintained, longitudinal collection of patient health information that is accessible and shareable across different healthcare settings, including hospitals, clinics, labs, and public health institutions.

It typically includes patient demographics, diagnoses, clinical notes, lab results, imaging reports, prescriptions, medication history, immunizations, allergies, past medical/surgical history, and referrals and discharge summaries.

The key difference between EHR and EMR (Electronic Medical Record) is that EMR is often tied to a single facility or care provider, such as legacy hospital software. EMR is a step-up from paper records, which are usually fragmented, hard to store and retrieve, and unsuitable for the digital ecosystem.

EMRs’ lack of interoperability necessitates an EHR upgrade, accompanied by a shift in health system culture toward data-driven, coordinated, and equitable care.

Bangladesh’s health record system is predominantly paper-based, and records are often incomplete, illegible, or lost, especially during patient transfers. Each health center maintains its records, with no standard format or shared system.

Patients usually carry handwritten documents or notebooks for continuity of care. Lack of prior history often results in duplicate tests and prescriptions, which contribute to both the delay of care and the increased cost of care.

Digital record-keeping systems do exist in some private care facilities, but they are often used in silos and cannot share information with one another. In most care facilities, manual documentation increases the administrative workload, leaving less time for patient care.

Aggregated data is not timely, accurate, or granular enough to support national health planning. As a result, outbreaks and drug shortages are often detected too late.

Introducing EHR can offer transformational potential across three key dimensions: improved care delivery, better health system management and planning, and stronger public health and resilience.

A patient-centric, longitudinal, and unified view of each patient’s medical history, regardless of where they receive care, reduces the chances of missed diagnoses and provides a holistic picture of drug interactions by tracking allergies, past treatments, and comorbidities.

Physicians can access real-time data from referrals, lab results, and imaging, even from remote facilities, which helps manage chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, HIV, TB).

Real-time dashboards on disease patterns, hospital usage, and medicine stockouts, among other metrics, enable authorities to more effectively plan workforce deployment, procurement, and infrastructure development.

Early signals from digital clinical records can trigger alerts (e.g., spikes in fever, respiratory symptoms) and can play a critical role in surveillance, prevention, and emergency response.

In Bangladesh, where resources are scarce, an EHR can maximize the impact of every healthcare dollar spent. It can bridge the rural-urban care divide and lay the foundation for universal health coverage.

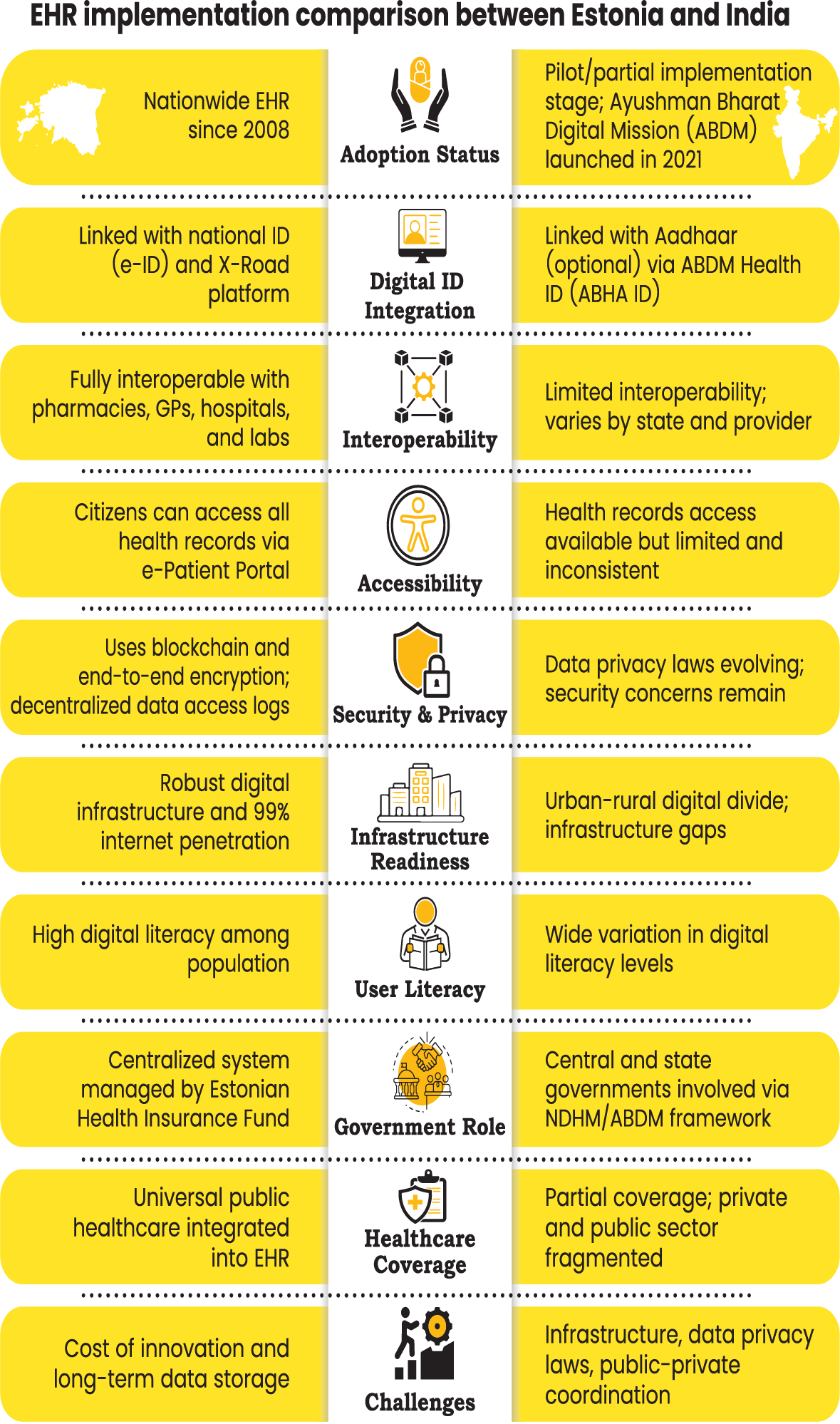

Case in point: Estonia and India

Dismantling an old juggernaut and installing a new way of providing health care is no cakewalk. Well, we can learn from successful implementations.

Estonia, one of the smallest countries in the world, with a population of about 1.3 million, opted to go digital-native by implementing a secure digital ID for its citizens.

The country then established a secure data exchange layer named X-Road, enabling public and private databases (such as health, tax, and population registries) to interoperate. They built a decentralized but interoperable EHR system.

In this system, each healthcare provider retains its internal systems, and a national health information exchange (HIE) connects all these systems through standards-based interoperability.

Health data is automatically uploaded to the central system and is available to authorized parties. Patients and only authorized care providers can access specific patient records, and all personally identifiable information (PII) is removed for macro-level reporting.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have India, with a population of 1.4 billion. In 2020, India initiated its ambitious endeavor to establish a federated, patient-centric, and standards-driven national digital health infrastructure under the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM).

Like Estonia’s case, India’s model does not centralize data. Instead, it focuses on interoperability, consent, and patient empowerment.

It has a unique digital health ID (ABHA ID) for every citizen, used to link and share health records securely. Participation in this system is voluntary and citizen-controlled, tied to Aadhaar or a mobile number.

Through a service named Ayushman Bharat Health Account, patients can access and share their health data across providers.

A federated network of health information exchanges allows different health IT systems (hospitals, labs, pharmacies) to share EHR data with patient consent.

The data is never stored centrally; instead, it resides with the providers. India has also developed a technology and policy framework called the Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) to give individuals full control over their data, including health records, financial information, and other sensitive data.

Under this consent framework, patients must give explicit, purpose-bound, and revocable consent before data is shared.

There are national registries of healthcare professionals, health facilities, and digital health applications that form the backbone for trust and interoperability.

The system has adopted Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), a global standard for EHR data, and provides open APIs for developers and health IT providers to plug into the system.

A strong public-private partnership involving health tech startups, government hospitals, insurance companies, and NGOs, along with a phased, voluntary adoption model and a sandbox approach, has enabled startups, hospitals, and vendors to test integration before production. This approach has brought over 500 million people to the system within just 5 years.

Roadmap for implementation in Bangladesh

For policies and governance, we need to establish and empower a digital health authority or steering committee with responsibilities that include setting standards, oversight, procurement, audits, and partnerships.

Along with that, proper data protection laws need to be enacted to ensure patient privacy, consent, and security, and define ownership and stewardship of health data (patients, providers, government).

A national ID-based digital public infrastructure should be created that can uniquely identify patients across systems.

Adopting global health data standards such as HL7 FHIR, LOINC, ICD-10, and SNOMED CT should be the way to go instead of reinventing the wheel. When selecting tools and platforms, proper due diligence should be done to avoid vendor lock-in.

We should leverage the pervasiveness of cell phone connectivity and develop cloud-native mobile apps that both patients and healthcare workers can use. The tools and platform themselves will be useless unless we also work on capacity building for the healthcare workforce.

Dismantling an old way of doing things should come with a well-trained, energetic workforce who will be willing to be the pioneers of the new system. Continued training of current workers should be augmented with the inclusion of digital health topics in medical and nursing school curricula.

Starting small by choosing a few pilot projects and then scaling them up region by region would be the way to go.

Starting with the public health system, largely run by the government, and then incorporating private clinics, labs, and pharmacies through open APIs, certification, and partnerships, can ensure both horizontal and vertical scaling.

In the near future, regulatory nudges such as tying hospital operating licenses to EHR adoption can help increase the footprint. We should view this not from a product perspective, but rather as a long-term public infrastructure project.

Successfully implementing an EHR system depends heavily on meaningful collaboration between the public and private sectors.

The government must establish a national vision and digital health strategy, developing standards, interoperability protocols, and data governance policies. Additionally, investment in digital public infrastructure, such as health IDs and health information exchanges, is necessary.

Public hospitals and primary care centers can be the early adopters.

For the private sector, partnering with the government on this cause is not just about philanthropy. It will lead to efficient operations and improvement in patient care and outcomes, which ultimately impacts the bottom line.

Healthcare providers should invest in digitizing patient care with their own EHR systems and integrating them with the national health infrastructure. Health IT companies and software vendors will have many opportunities to develop EHR platforms, analytics, AI tools, and patient engagement apps.

Health systems built on paper records, fragmented data, and manual workflows are not only inefficient; they fail to meet the needs of patients, providers, and policymakers.

The government must make EHR a national priority and create an enabling environment by enacting laws and drafting governance policies. For the private sector, it is a new market to explore and innovate.

Healthcare providers should become champions for EHR adoption, as this will improve patient care and outcomes significantly. For citizens, they should advocate strongly for better, more transparent healthcare through digital accountability.

Sameeul Bashir Samee is a computational scientist currently working at the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like