Environmental disclosure reshaping business norms

May 30, 2025

Every time the question is raised regarding why disclosure regarding compliance reporting from an environmental angle is required, the 2013 Rana Plaza incident must be mentioned. Call it sustainability reporting, ESG reporting, or environmental disclosure and compliance reporting; the point is straightforward–it is about a company’s seriousness about the factors tied to governance, social, and environmental angles. All these can be seen from one common lens: sustainability.

From a regulatory point of view, there is a surge of frameworks and standards worldwide under many different names and forms. We have the Sustainability Code in Greece, the Energy Transition Law in France, the King IV Code of Governance in South Africa, the German Due Diligence Act in Germany, and so on.

Even on a broader spectrum, we see European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) and the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in the European Union, and internationally, we have GRI Standards. There is also the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), both aimed at investors.

What is it, actually? Is it a mere tick-the-box thing? Or is it beyond that? Basically, it serves as a communication and disclosure tool, which is designed to increase corporate transparency about an organization’s performance in the environmental arena (scope 1,2,3 emissions, sustainable practices, environmental footprint), along with social factors (the impact on the broader community, workplace diversity, cultural indicators) plus how it is being run or governed ( fair and just labor practices, shareholder rights, diversity and inclusion).

It is a process for measuring and attributing greenhouse gas (GHG), climate, and environmental impacts and outcomes to an organization’s direct actions and business operations.

But the question remains: Why do we need it in the first place? First, let us break the stereotype that it is just another fad or a mumbo jumbo riding on the wave of other buzzwords.

Owing to the rapid expansion of digital infrastructure, investors worldwide are interconnected, and their ‘wokeness’ in general is bringing back the age-old original concept that a business or a company is not only what number it creates but also the value that the consumer gets from it. That goes beyond the number crunching and lies in the grey world of trust. Thus, an ‘evil’ company with good numbers will alienate potential customers if they are found to be associated with something that shakes the confidence of the mass investors.

At the same time, a different sort of psychological bias also comes into play here. Inadequate reporting doesn’t just impact the financial sphere; it also erodes public trust. Companies that cloud or downplay their environmental impact cause reputational damage, both domestically and on the global stage.

In an era when consumers are increasingly eco-conscious, such opaqueness can lead to diminished market share and profitability. While ignoring this might seem wise in the short term, in the long term, as the trend is leaning towards the green faction, that is the future to go for.

Transparency in sustainable practices fosters trust among consumers, investors, and the broader community. When companies openly disclose their environmental impact and mitigation strategies, they commit to sustainability and responsible business practices.

Accurate and detailed environmental reporting provides the data necessary for informed decision-making and strategic planning. This, in turn, infuses trust in the investors’ minds, which transforms into loyalty. This also surges the brand image.

Showcasing their efforts to reduce their carbon footprint and energy usage, they also improve their corporate reputation, ultimately enhancing market trust. This creates the scope for government incentives and subsidies, along with ethical investment funds.

However, these are all external benefits. There is also an internal angle to them. Since this arena is relatively new, it helps create market differentiation and drive innovation in products and services. Ultimately, this helps companies limit the many types of value chain risk, creating better, stable, and long-term shareholder value. The product’s value is why a consumer might be retained.

A misguided concept raised in cases like this must be addressed. No, environmental reporting/sustainability reporting/ ESG reporting does not necessarily paint the world with more colors or make everything sustainable in a snap, especially when this reporting is being done just for the sake of reporting.

It establishes awareness. It is more like a seed, biding its time to eventually become a tree; it will not start giving us fruits from the get-go. As part of sustainability reporting, when a company provides information on its environmental performance over time, it encourages other companies to jump on the bandwagon. This promotes healthy competition for adopting circular business practices and sustainability targets, acting as a catalyst for future investments.

Bangladesh has also taken baby steps in this regard since several regulatory interventions by the concerned regulatory bodies have addressed this issue. For instance, Bangladesh Bank launched its circular in 2008 titled “Mainstreaming corporate social responsibility in banks and financial institutions in Bangladesh.” It pondered the notion of taking sustainability reporting seriously in Bangladesh for the first time.

In 2011, BB issued a green financing initiative to support the financing of environmentally friendly projects and introduced the notion of green banking in Bangladesh. In 2020, the bank issued a ‘Sustainable Finance Policy’ to incorporate the act “to accommodate Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues” (preamble) in the portfolio of banks and financial institutions in Bangladesh.

Since the money market and the capital market go hand in hand in the financial scenario, the regulator of the capital market, the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission (BSEC), has introduced mandatory disclosures of the corporate governance issues for the listed companies. This directive has been amended several times with the incorporation of necessary codes. However, the point to be noted is that this does not touch all the issues regarding the broad spectrum of ESG.

Despite all these interventions, at times mandatory, being put in place to uplift the spirits of the investors, the scenario of reporting of these sorts in Bangladesh is quite disappointing. These are mostly unreliable, at times poor, and historically, some have been quite politically motivated.

In many companies with highly concentrated family ownership, different aspects of the reporting become blurry, with the stake and necessity of the said family becoming more important than following some code. A key finding here is that the companies are willing to store and record data from the financial reporting angle (even if they cook it to come out as profitable), but when it comes to sustainability reporting or ESG reporting, attempts are seldom made to develop and store them.

As of 2022, only a disappointing 11% (roughly 40+ but still hovers below 50) of the companies included sustainability in their annual reports and dedicated exclusive reports. Some notable examples are IDLC since 2010, Bank Asia since 2013, and Robi Axiata since 2014, which have been the early adopters of reporting.

If we segregate the sectors, the telecom and banking sectors will be at the top, with 34% and 20%, respectively. The compliance in the telco sector can be attributed to being tied to the parent company on an international basis. As for the banks, the effect shows the steps taken by their central regulator, the Bangladesh Bank.

However, the case of the unlisted companies is even worse, as they have not even reached the mark of 20. Overall, if we count the total number of sustainability reports, only for 3 years did it go above 50 out of the 400+ companies. These include the mandatory annual report, which mentions their sustainable practices, and exclusive reports, which are published solely to showcase their sustainable practices.

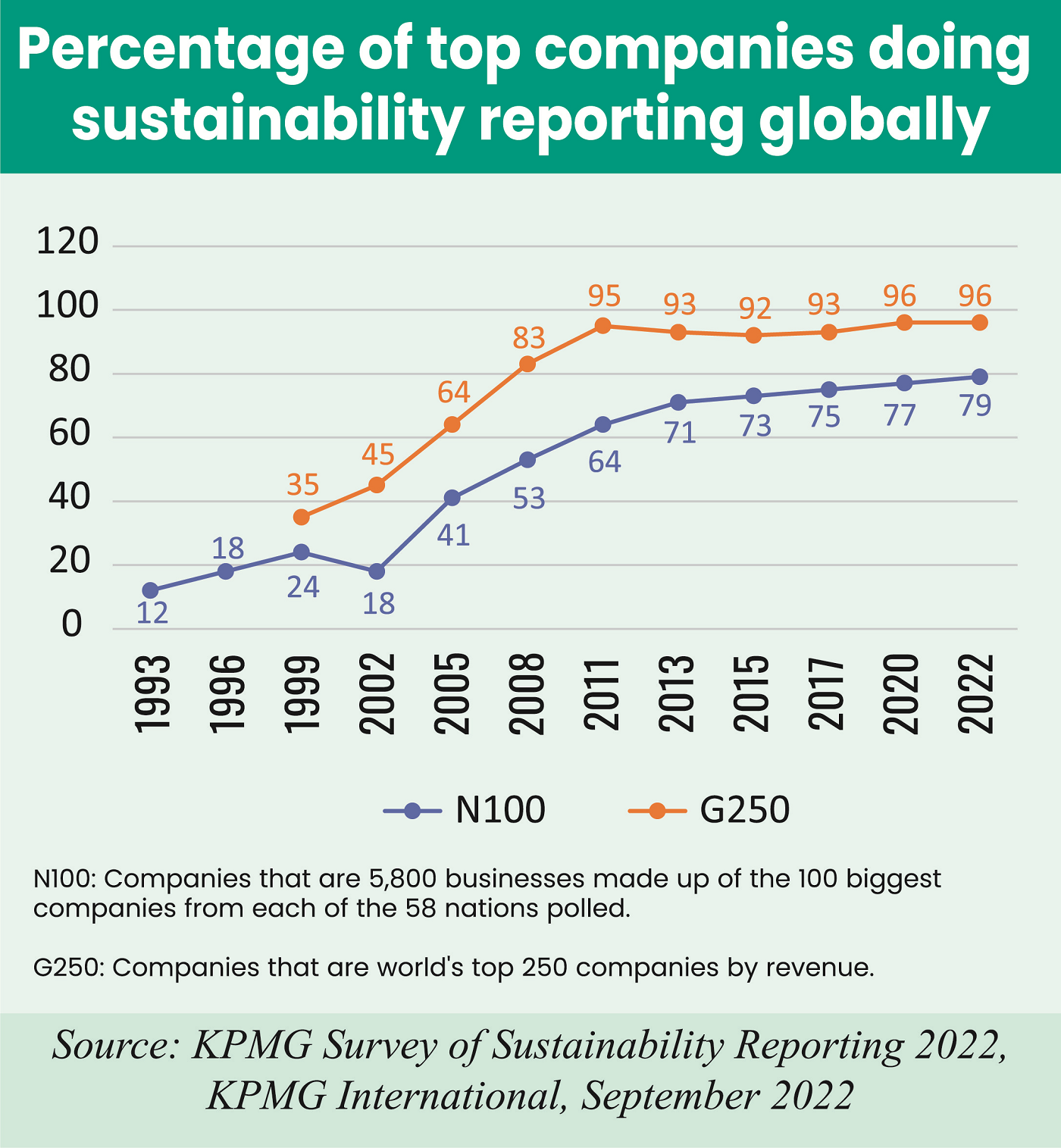

This is poor when considered in the global arena. As per the KPMG survey of sustainability reporting 2022, among the N100 companies (a worldwide sample of the top 100 companies by revenue in 58 countries, territories and jurisdictions, for a total of 5800 companies), a staggering 96% have been doing sustainable reporting.

This is on a global scale. Even if we zero in on the Asia Pacific region, among the top 1340 companies, 89% are doing sustainability reporting. If we shift focus to the G250 (the world’s 250 largest companies by revenue based on the Fortune 500 ranking), we will still see a decent 79% doing sustainability reporting. This shows a stark difference in perception regarding the importance of sustainability reporting from our country to the outside world.

Why are we reluctant? Is it just to conform to the generic notion that we are inherently corrupted? Or are there any other forces at play here? Well, for starters, if we shed the generic bias, we can find that for organizations, selecting which sustainability reporting standards and frameworks to use is an important early step on the path to improving environmental performance.

Here lies the catch. There is an alphabet soup of different standards and frameworks to follow. Today, there are more than 600 different sustainability reporting standards, industry initiatives, frameworks, and guidelines around the world, making sustainability reporting a complex, research-heavy, and repetitive process.

For this reason, unlike financial standards, this doesn’t yet operate with the same transparency, consistency and interoperability. So, the companies are in a fix on understanding the reporting methodology and relevant standards; they also have a lack of clarity about the evolving trend of the stakeholder expectation towards striving for sustainability.

Plus, the sheer lack of regulatory requirements (which is gradually improving), when compared to the financial requirements, also paves the way for an escape. So what do the companies do?

They engage in some greenwashing and CSR activities and think that they have achieved something great. But the reality is often far from what is being perceived.

Galib Nakib Rahman initially worked as an MTO and, later, as an executive officer with Prime Bank PLC. He is currently a senior executive with the Dhaka Stock Exchange in the Corporate Governance and Financial Reporting Compliance Department in the Regulatory Affairs Division.

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like