The making of Asia’s Detroit

August 08, 2025

Name a tourist hotspot, and Thailand is surely on the list. Ranked as the 8th most visited country in the world, Thailand has welcomed 12.09 million foreign tourists in the first four months of 2025, generating 576.85 billion baht in revenue—a 5.24% year-over-year rise.

But another genie has been there beyond the beaches and temples – the automobile industry.

Over the years, Thailand has become the world’s 10th-largest car producer, earning the moniker ‘Detroit of Asia,’ claiming a solid 2% of global output, and cementing its role in the engine room of the global automotive economy.

Thailand now ranks among the top ten vehicle manufacturers worldwide. The country’s transformation into an automotive manufacturing powerhouse is no accident but the outcome of decades of strategy, policy innovation, and public-private collaboration.

Inside the Thai automotive industry

Over half of Thailand’s automobile production is intended for export. The country’s automotive industry is valued at approximately $12.67 billion. The nation produced about 2.55 million automobile units in 2023, and by 2028, it is expected to have increased to 2.98 million.

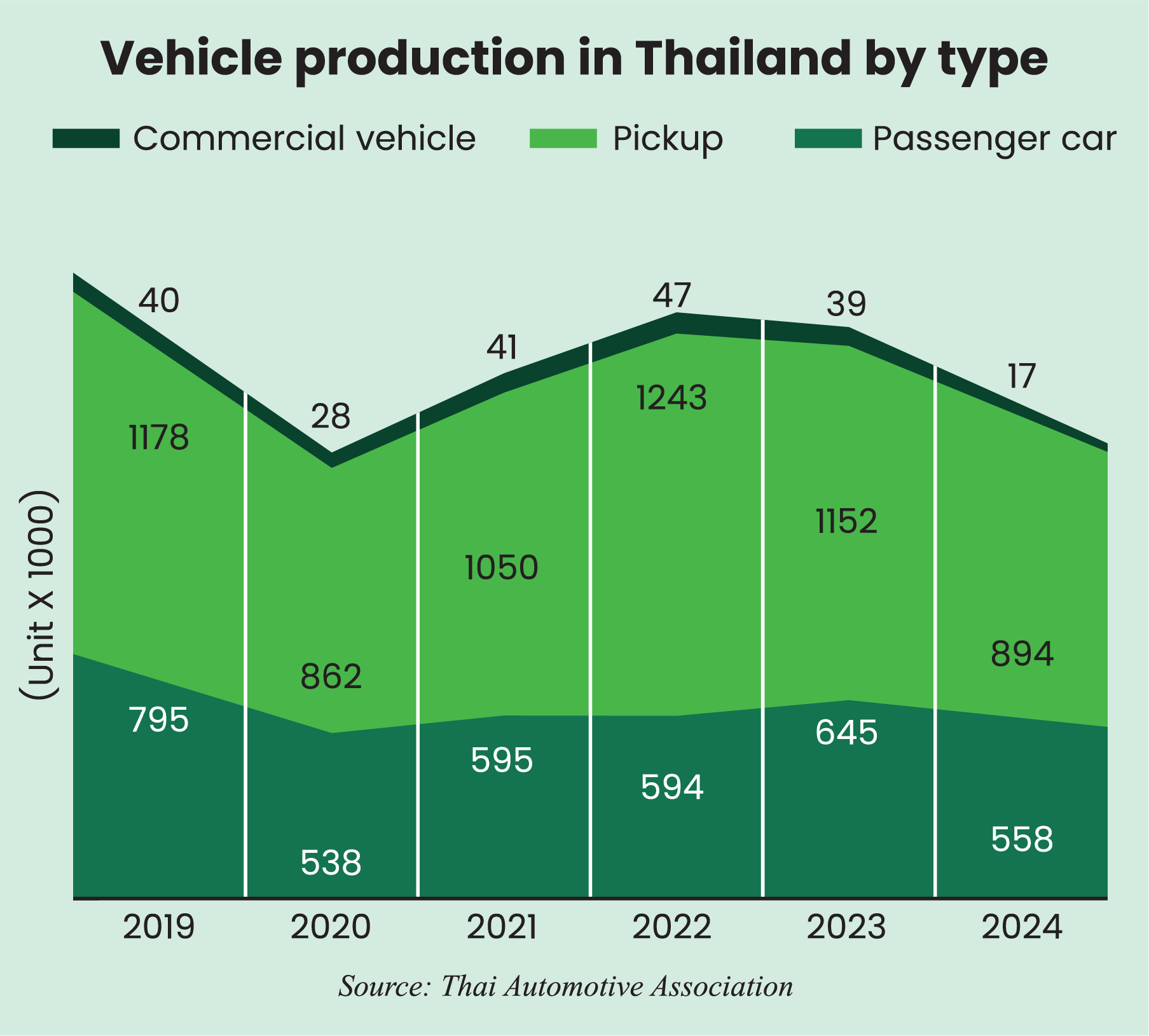

In 2024, the industry produced about 1.47 million vehicles, of which 1.02 million were sold for export, and 0.57 million were distributed domestically, as previously stated.

Major international automakers like Ford, Mazda, Mercedes-Benz, Honda, Mitsubishi, Isuzu, Toyota, and newcomers from China’s EV industry share this dominance.

Thailand also produced about two million units of motorcycles in 2023. The country aims to become a leader in electric vehicle (EV) production, with a policy goal of making 30% of all vehicle output electric by 2030. This vision is part of their 30@30 strategy.

Production in numbers

In Thailand, pickup trucks account for 61% of all automobile production, with passenger cars coming in second at 38%, and other commercial vehicles, such as vans and buses, contributing 1%.

In 2024, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) only accounted for 0.7% of all automobile production. Domestic auto sales in 2024 were 572,675 units, a 26.2% decrease from the year before.

The market was dominated by passenger cars (340,056), followed by pickup trucks (200,190) and other commercial vehicles (32,429). In terms of electric vehicles, 71,520 BEVs were registered in 2024, a 6.3% decrease from 2023.

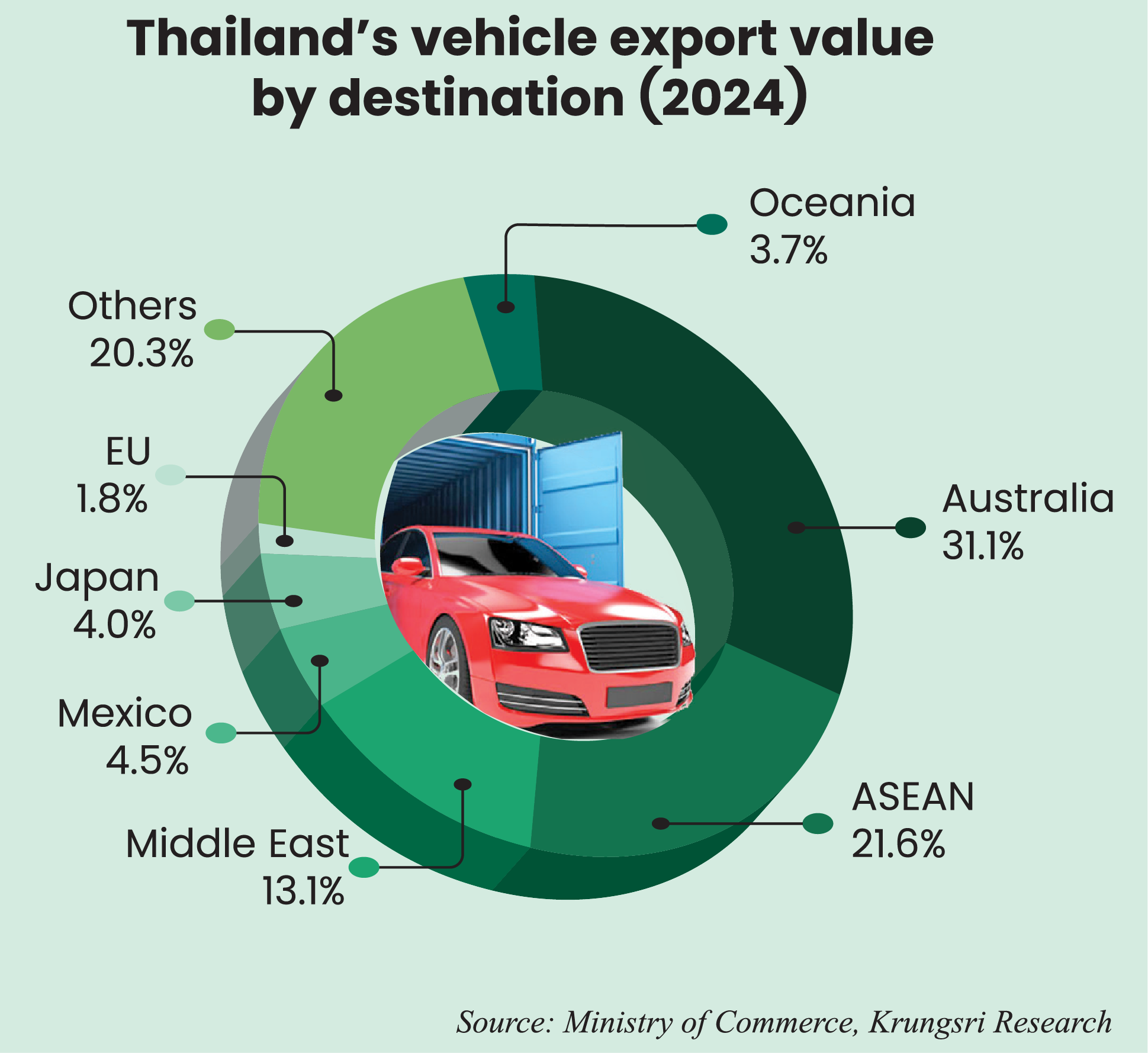

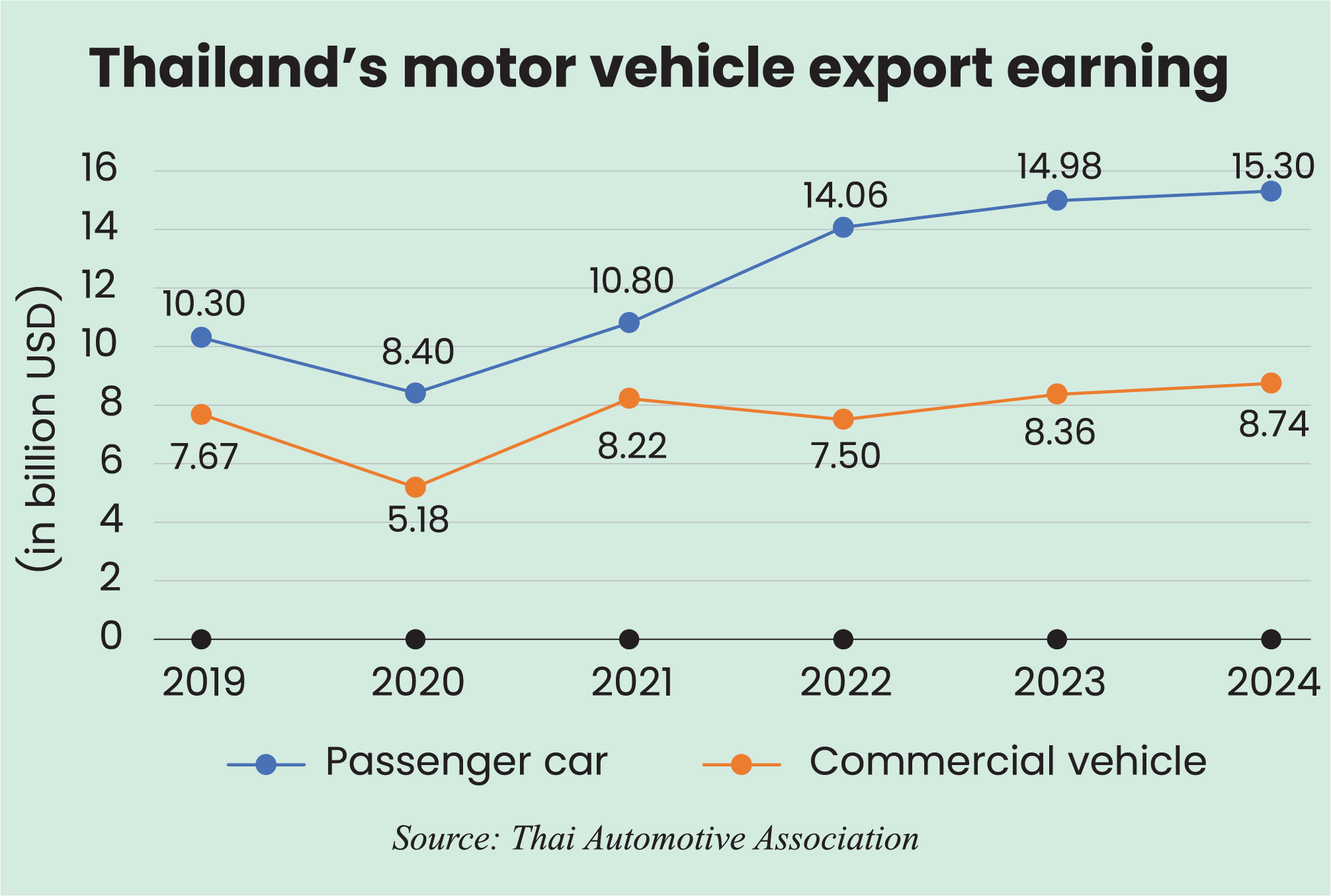

In 2024, Thailand exported over a million automobiles, valued at approximately $24 billion. Passenger cars accounted for 64% of this, while commercial vehicles made up 36%. The United States, China, Japan, Australia, Malaysia, and India were the biggest export destinations.

Supply chain and quality standards

Thailand has one of Asia’s most regionalized automotive supply chains. With the support of about 1,500 ISO-certified suppliers, the nation has successfully localized about 80% of its car parts.

While there are more than 1,100 Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers, there are about 720 Tier 1 suppliers. The structure is supporting the conventional Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicle market and also adjusting to the new EV ecosystem.

Financial incentives, including subsidies of up to 100,000 baht (approximately US$2,950) for EVs with batteries exceeding 50 kWh, excise tax reductions from 8% to 2%, customs duty cuts of up to 40%, and local production mandates for foreign manufacturers, are all part of Thailand’s ambitious EV transition.

While shifting towards electrification, Thailand aims to maintain its leadership as an original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

Strategies behind the progress

Thailand’s emergence as an automotive hub is not solely due to its strategic location in Southeast Asia. There are well-crafted policies behind.

Thailand offered substantial corporate income tax exemptions, up to 15 years in certain situations, as well as import duty waivers for raw materials and machinery. The Thailand Board of Investment (BOI) plays a vital role in this.

The government provides non-tax incentives such as land rights, 100% foreign ownership, and expedited immigration processes for foreign experts. Thailand made the early switch to an export-led growth model from import substitution.

Thailand also enacted high import tariffs and local content requirements (LCRs) early on to give a necessary push. Later, the country opened its market and signed several free trade agreements (FTAs), including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the ASEAN-Japan Economic Partnership, which provided Thai-made automobiles with access to international tariff advantages.

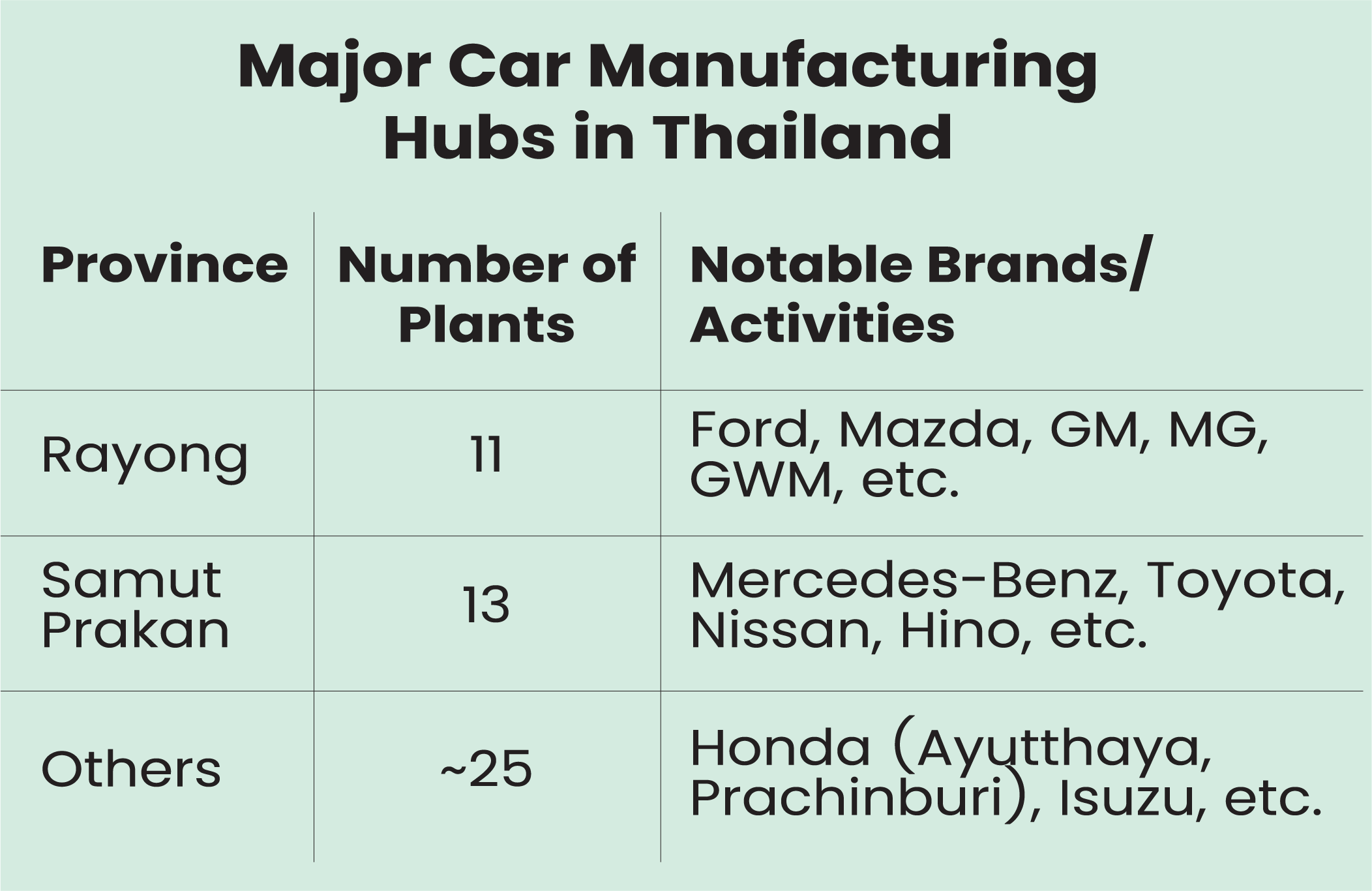

Thailand has a combined 57 manufacturing facilities, 24 of which are located in Rayong and Samut Prakan, the country’s top auto hubs.

Import-export operations are facilitated by the proximity of these clusters to deep-sea ports and their strong logistics networks. The Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) supports high-tech manufacturing like electric vehicles.

To encourage the production of small, fuel-efficient cars, Thailand initiated the Eco Car Program in 2007. Automakers that took part in this program gained market advantages and tax breaks.

More recently, the nation implemented EV-specific policies, known as EV 3.0 and EV 3.5, which include tax breaks, subsidies, and requirements that automakers produce two EVs in the country for each one that is imported.

By 2030, these initiatives hope to produce 675,000 electric motorcycles and 725,000 EVs annually.

Becoming an OEM powerhouse

There are 25 automakers in Thailand, which are split between 12 foreign-owned, nine joint ventures, and four domestically owned businesses. These consist of 10 administrative headquarters and 49 manufacturing plants, totaling 57 automotive OEM facilities.

The industrial map is dominated by Samut Prakan and Rayong. Businesses can concentrate on both domestic and foreign exports thanks to this spatial distribution.

On that note, Thailand’s rise to become a leading Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) can be traced through five strategic phases.

Phase 1: Import substitution (1960s–1970s)

The government started implementing measures to encourage domestic production in place of imports. Thai companies and foreign automakers formed joint ventures in response to high tariffs and local content requirements.

Phase 2: Building supplier base (1970s–1980s)

Stricter LCRs were put into place in the 1970s and 1980s. This forced international automakers, especially the Japanese, to create local supplier networks. Local production of parts like batteries and radiators bolstered the domestic value chain.

Phase 3: Liberalization and global integration (1986–1999)

Thailand liberalized its automobile industry and opened its market to foreign investment in the mid-1980s. With reductions in import taxes and the elimination of some LCRs, the integration of the Thai industry into international production networks, especially those of the United States and Japan, was facilitated.

Phase 4: Cluster formation and OEM specialization (2000s–present)

Tightly integrated automotive clusters emerged in the early 21st century. Here, suppliers, logistics companies, OEMs, and even training facilities coexist. Thailand has become a global hub for automobile OEM exports, in addition to being a regional center.

Phase 5: Electrification (Present)

Thailand is currently investing state funds to increase its EV capacity. Industrial strategies, such as ‘Thailand 4.0,’ and national roadmaps, like ‘EV Roadmap 2035,’ place a strong emphasis on high-tech production, sustainability, and international competitiveness.

Thailand’s automobile industry is still robust and progressive. Long-term forecasts remain positive despite sporadic downturns, such as a decline in domestic sales or EV registrations.

The nation’s automobile industry is well-suited to the cycles of global demand, with major export markets including the US, China, and Japan. Its ability to switch to electric vehicles and adjust to shifting consumer preferences will determine its future growth.

For emerging economies seeking to establish their industrial bases, Thailand’s automotive journey offers a compelling case study.

Syed Raiyan Amir is a Senior Research Associate at the KRF Center for Bangladesh and Global Affairs (CBGA). With a strong background in international affairs, he previously served as a research assistant at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Republican Institute (IRI).

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like