Why Bangladesh needs stricter pharmaceutical regulations

May 11, 2025

The pharmaceutical industry operates within a complex and multilayered supply chain involving various hidden intermediaries. How does a medicine reach the patient after being manufactured in a lab (assuming the mandatory clinical trials prior to distribution)?

Pharmaceutical manufacturers either distribute their medicine in bulk to a wholesale intermediary or directly form contracts with hospitals and local pharmacies. Pharmacies and healthcare facilities receive the medicine from those manufacturers or intermediaries and administer it to patients.

However, this process is more intricate than it appears, as storage, distribution, and pricing are managed by wholesalers and healthcare providers. Therefore, it’s evident that complex drugs are rarely handled by pharmacies or hospitals with poor drug management systems, and these pharmacies need extra monetary aid to store critical medicines.

That’s when Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBM) come in. They negotiate discounts and rebates with manufacturers on behalf of pharmacies/hospitals, influencing drug pricing and formulary placement. Through negotiations, the PBMs then transfer some of the maintenance cost to the customers, who basically co-pay the medicine distribution cost without the full knowledge of the payment terms.

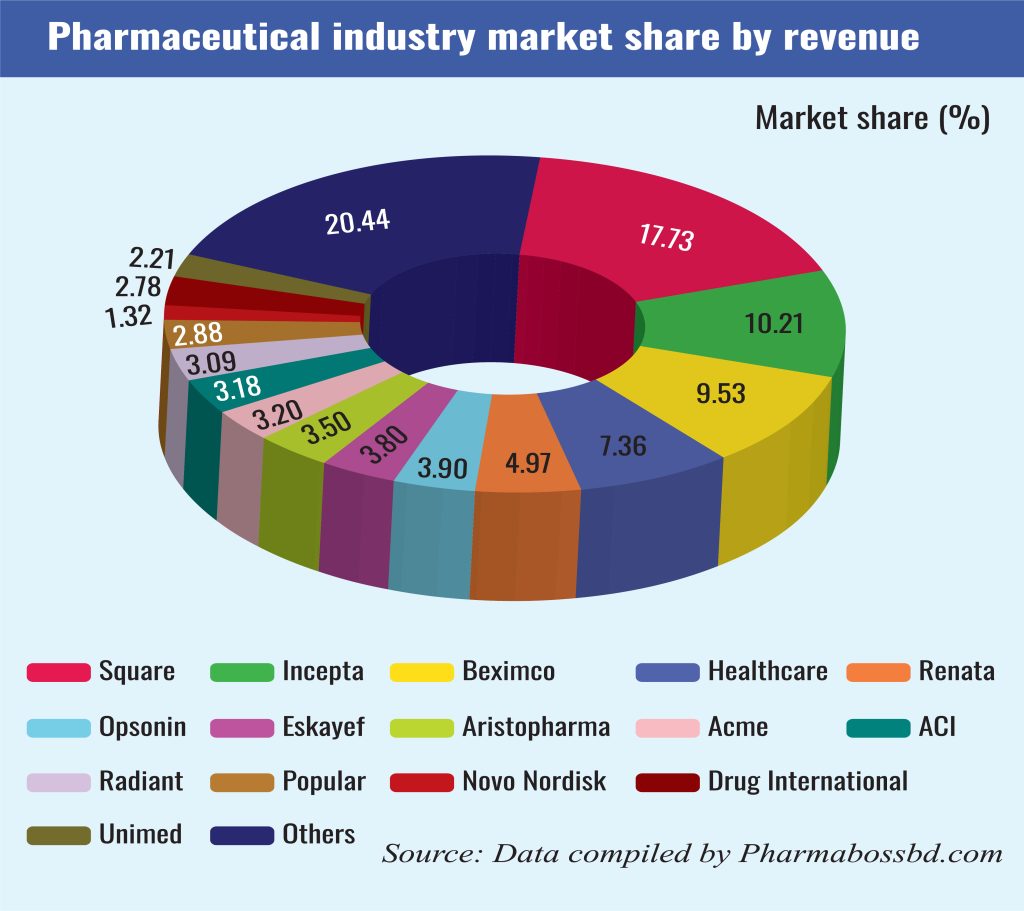

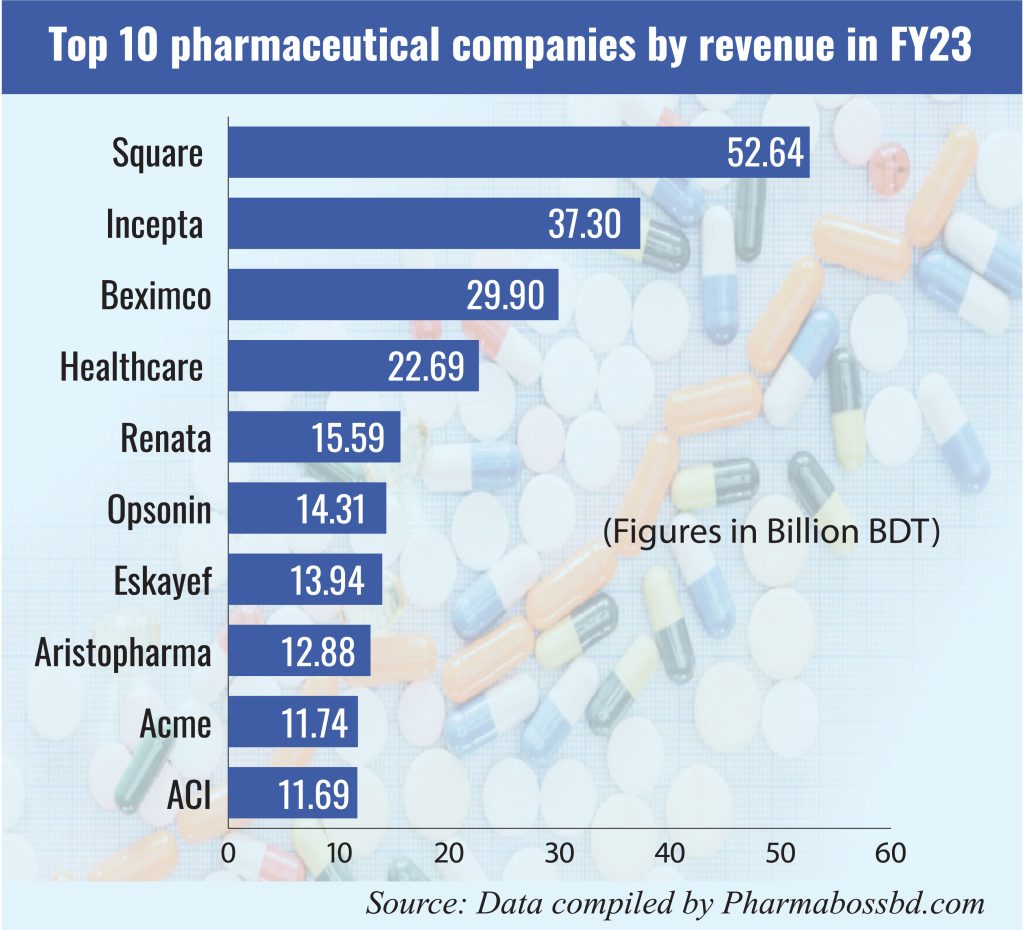

Bangladesh’s pharmaceutical industry has witnessed remarkable growth, evolving into a nearly self-sufficient sector that meets approximately 98% of the country’s domestic demand for medicines. This achievement is attributed to over 300 pharmaceutical companies operating nationwide, with the top ten producers accounting for roughly two-thirds of the market share. Local pharmaceutical products are also exported to over 150 countries and are forecasted to generate Tk 505 billion in revenue this year.

However, heavy dependency on Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) imports has been a significant challenge for the industry as local API production has not been possible yet. Lack of compliance with international standards, poor implementation of drug laws, poor administrative structure of the national bodies controlling medicine, lack of quality research and development initiatives, and export barriers resulting from the inefficiency of the local manufacturing sector are some prevalent issues.

Regulatory framework and current practices

The Directorate General of Drug Administration (DGDA), under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, serves as the principal regulatory body overseeing the pharmaceutical sector in Bangladesh. It was established in 1974, immediately after independence. Under its jurisdiction, local manufacturers could produce drugs that were patented by other countries. This initiative helped remove harmful drugs from the local market and ensured cheaper access to life-saving critical medicine.

One of the agendas in the 2016 Drug Policy was to build DGDA’s capacity for its transformation into a National Regulatory Authority (NRA, responsible for product evaluation and ensuring global standards) for drugs in Bangladesh, its subsequent recognition as an NRA by the World Health Organization (WHO), and membership of the Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention and Pharmaceutical Inspection Cooperation Scheme (PIC/s).

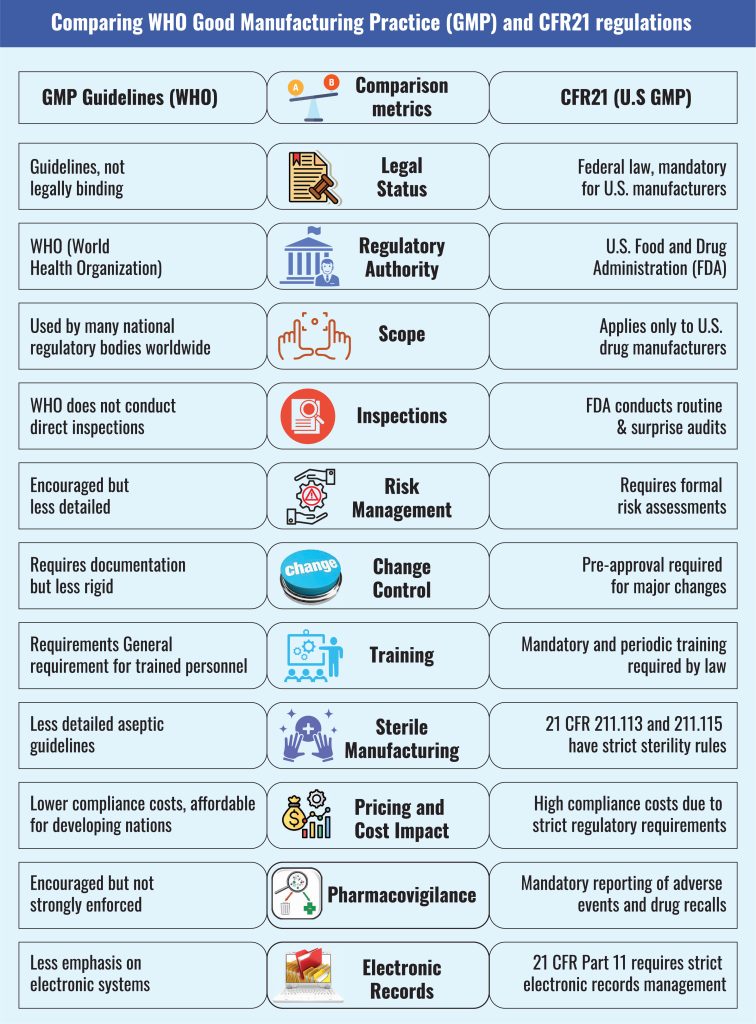

Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), also known as current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), is a quality assurance framework that ensures medicinal products are consistently produced and controlled to meet quality standards. It covers production, quality control, personnel, premises, and materials, with legal aspects governing distribution, contract manufacturing, and defect responses.

WHO first introduced GMP in 1968, integrating it into the WHO Certification Scheme in 1969. Over 100 countries have incorporated WHO GMP into national regulations, influencing global pharmaceutical quality and vaccine prequalification for UN procurement, and Bangladesh is one of those countries.

WHO’s GMP guideline has 20 chapters concerning regulatory requirements, quality assurance, manufacturing processes, personnel training, equipment, containment, validation, and quality control. It is a reference for national regulatory authorities (NRAs) and manufacturers to ensure the safety, efficacy, and consistency of biological products.

Bangladeshi pharmaceutical companies are evaluated using this guideline. Bangladesh also follows the National Guideline on the Pharmacovigilance System, which informs healthcare professionals about detecting, assessing, and preventing adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and medication errors. The guideline emphasizes risk management, reporting procedures, and compliance with international best practices as outlined by WHO and the Federal Drug Authority (FDA).

Exploring better

While GMP is recognized globally, emphasizing that it is followed by over 100 countries worldwide, it lacks certain regulatory vigor that makes this practice vulnerable to malpractice.

GMPs were meant to operate in the developing world, where public health-related administrative structures are prone to external and internal threats. In a workshop related to GMP Implementation in Biological Products in 2018, DGDA represented Bangladesh, and it was mentioned that Bangladesh faced a documentation gap, lacked qualified personnel, and had faulty pharmaceutical inspection processes.

As detailed in the chart above, the United States has incorporated the GMP related to drugs and food in its Code of Federal Regulations (CFR; rule no.21), making it a federal requirement, not voluntary compliance.

The voluntary nature of the GMP adoption and enforcement rules makes it difficult for countries like Bangladesh to control the quality of the pharmaceutical sector. Bangladesh’s Drug Act of 1940 and Drug Control Ordinance of 2006 solely focused on drug quality, whereas the Drug Policy of 2016 described the rules and regulations directed at manufacturers and policymakers.

However, the Drug Act of 1940 and the 2006 ordinance did not mention punishment for drug adulteration. After the 2016 revision, the DGDA has occasionally suspended a few pharmaceutical companies on the grounds of manufacturing malpractice. There has only been one case of 10 years imprisonment for drug adulteration. Hence, the quality of the actual ‘manufacturing quality check’ done by the DGDA under Pharmacovigilance guidelines begs further questions.

It made sense to protect Bangladesh’s local pharmaceutical industries at the initial stages of independence when the nation was trying to rebuild itself. But now, in this global climate, Bangladesh has no other option but to improve its local drug distribution and manufacturing practices and compete with the international giants- point in case the recent Indian visa crisis and increasing concerns raised by Indian pharmaceutical companies operating in Bangladesh in this turbulent political climate.

Like many developing countries, Bangladesh’s pharmaceutical industry is dominated by the private sector, and thus, misuse and malpractice related to pharmaceutical services are frequently left unnoticed.

Adhering to the CFR21 rules and installing similar stringent policies in Bangladesh will have a far more effective impact on improving this sector. Implementing such a rigorous and legally binding framework is laden with challenges that have made headlines in the recent past, including incidences of bribery, syndicate, and money laundering in the name of tertiary hospital operations, to name a few.

The local pharmaceutical manufacturing giants, through the government, have managed to impose a ban on imports of locally produced medicine, shrinking the market and concretizing the monopolization.

However, the recently published Task Force report on ‘Re-Strategizing the Economy and Mobilizing Resources for Equitable and Sustainable Development,’ which informs the interim government of pressing challenges and a way forward, has emphasized the need for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the healthcare sector—an initiative that the national manufacturers have opposed for obvious reasons.

For too long, Bangladesh’s pharmaceutical industry has been receiving incubator services. FDI focusing on institutional capacity development of healthcare facilities, R&D, and skills development could be one of the many ways to help this important sector.

If the sector becomes competent enough to follow the CFR21 standards, it will open a huge export market for Bangladesh in the U.S. If competition is brought back in this sector, people in Bangladesh will no longer have to rely on expensive medical treatments abroad.

Sharmin Jahan Juha is currently working at the International Labour Organization. Her research interests involve issues related to public health, business and entrepreneurship, public policy, and investment. She has 7 years of experience working in areas related to workplace compliance, policy formation and public communication.

Most Read

Electronic Health Records: Journey towards health 2.0

Making an investment-friendly Bangladesh

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

Bangladesh facing a strategic test

Bangladesh’s case for metallurgical expansion

How a quiet sector moves nations

A raw material heaven missing the export train

Automation can transform Bangladesh’s health sector

A call for a new age of AI and computing

You May Also Like