Political instability, not policy deficit, is holding back growth

November 25, 2025

Bangladesh today stands at a critical juncture, facing the twin pressures of LDC graduation and global economic uncertainties, while grappling with structural challenges in banking, energy, and private sector growth. To delve into these pressing matters, we turn to the expertise of Dr. Shahadat Hossain Siddiquee, a respected academic and commentator on the country’s economic affairs.

Dr. Muhammad Shahadat Hossain Siddiquee is a distinguished economist and professor of economics at the University of Dhaka. Holding a PhD in development policy and management from the University of Manchester, UK, he also earned a master’s in economics of development from Erasmus University Rotterdam and earlier degrees from the University of Dhaka. Alongside his teaching duties, he is a Senior Research Fellow at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD).

Amirus Salehin Ha-meem has conducted the interview.

Bangladesh’s private sector has been struggling since the pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war arrived before it could heal. Now, the impending graduation from the least developed countries category (LDCs) is adding to these challenges. Do you think our private sector is prepared to absorb the initial pressure brought by LDC graduation?

This is an important question, especially considering the LDC graduation. It would be beneficial for us to postpone it. However, the government is for LDC on time, which presents a significant challenge for us. Now the question is: why do we see it as a challenge?

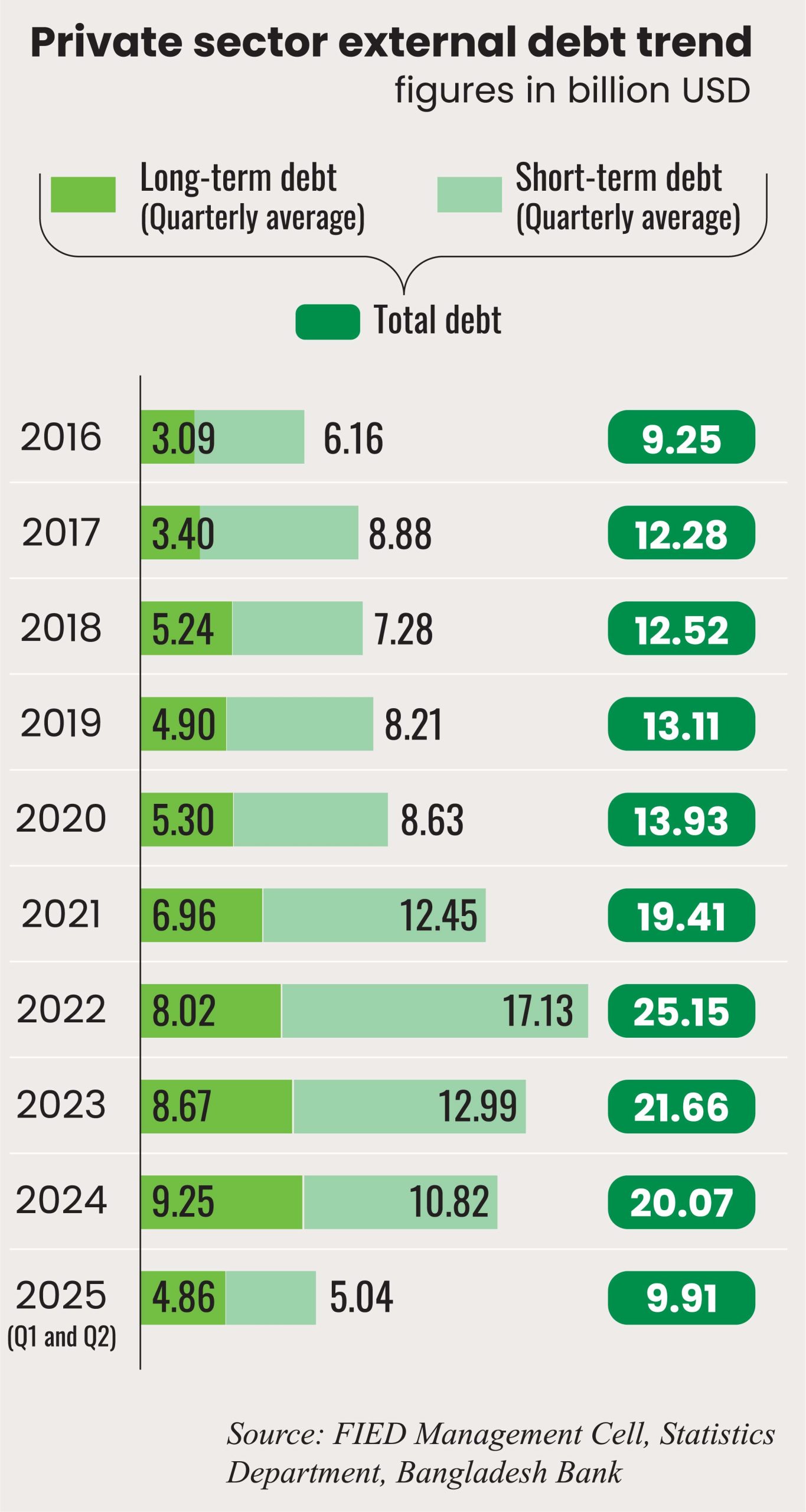

The first reason is that we haven’t yet obtained the growth potential of Bangladesh that we had before COVID-19. The country had the resilience to withstand pressures and could absorb any foreign shock. However, subsequent post-COVID-19 issues like the Russia-Ukraine war, the Middle East crisis, and most recently, Trump’s new tariff policy have seen the country lose its momentum.

The investments we are getting are not supporting our growth; or simply put, they are not influencing the growth curve enough.

However, there is a positive relationship between GDP and employment creation. GDP growth means the creation of employment opportunities. But our unemployment is on the rise, and many are not returning to the workplace. Even the graduate unemployment rate is rising. Almost 50% of the graduate population is unemployed.

Think about the demographic dividend; all the developed countries in the world have progressed by utilizing the demographic dividend. It is said that the demographic dividend comes to a country only once, and only those who can catch it can ride on the wagon of development.

If we fall into Malthus’s lower living income trap, it may not be possible for us ever to become a developed country because a big innovation-driven push is required.

Unfortunately, creative minds are not well-utilized in our country. I fear that Bangladesh might miss this demographic dividend and fall into the lower-income trap in the long run. Hence, if we can graduate from LDC after a few years, we could enjoy the benefits of a favorable market system for a while longer.

Now the question is whether Bangladesh is ready to take on the challenge. We are deciding on LDC graduation at a time when the country’s financial sector is in a mess. It is a big concern how the government will face newer challenges (stemming from LDC) while one-third of its disbursed loans fall under the non-performing category.

If we consider poverty reduction, our extreme poverty rate must be very low (close to 3 percent) to become a middle-income country. The daily income threshold is no longer $2.5, but $3, per international standards. And if you convert USD to taka, it depreciates by 40%, which means people need more money to remain above the poverty line.

In addition, Bangladesh falls in the ‘vulnerable’ category in the Vulnerability Index, also consistent with the World Bank measurements.

Non-poor refers to those vulnerable to falling below the poverty line due to minimal economic shock. Also, our standard of living is lower on average than that of other middle-income countries. There will be a massive difference if we compare it to upper-middle-income nations. To reach that level, we need a huge amount of investment and, at the same time, accountability and responsibility in economic institutions, neither of which is visible.

I think the biggest reason behind this is political instability, the responsibility of which lies with the interim government. It failed to live up to expectations. Therefore, the big challenge for the government is to make strategies to move forward with all, peacefully.

While reduced US tariffs are being celebrated, the country could face increased tariffs from the EU, Canada, and other nations after LDC graduation. Considering this scenario, what’s your verdict on LDC graduation next year? Should Bangladesh consider delaying it?

While the global situation is worsening, Bangladesh, however, has benefited in some cases. For instance, the Trump tariff has been reduced to 20% after negotiations, whereas a 50% tariff has been imposed on Indian products. As a result, Indian orders are moving to Bangladesh and Vietnam. Since Vietnam has to pay slightly more tariff than Bangladesh, we get a comparative price benefit here.

Because it specializes in the RMG sector, Bangladesh holds a firm place compared to Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Cambodia. Ready-made garment exports to the US market have already grown by 20% in the January-June period this year. The US has a $78-82 billion RMG market, which is more than our total export value. After the recent tariff saga, we have the upper hand in this big market now. However, to implement it, the effective role of the private sector as well as the supervision and support of the state are needed.

Energy security is important for production. The private sector is eager to expand but requires a smooth flow of fuel and energy to operate at full capacity, which hasn’t been ensured yet. Indian and Chinese investment potential has increased now, but political stability must be ensured. And without energy security, expansion of industry, creation of employment, or restoration of growth is not possible.

Due to the demographic transition in the global market, the demand for labor will increase. Older people will leave the job market, and young people will enter, like we are witnessing in Japan. The demand for skilled workers will also increase in the US, Canada, and Scandinavian countries. So for Bangladesh, the key will be upskilling the youth.

Speaking of the threat of high tariffs from the EU and Canada, any type of tariff or tax hurts growth. Therefore, no other country in the world, except the US, will take such a risk.

The country’s energy sector has been a hoax – massive capacity but inadequate production. Businesses have struggled to continue full-scale production amid an inconsistent energy supply, while investors are daunted due to energy security and high pricing issues. Your suggestion?

The energy sector is run by the state, and over time, the sector has become profitable. The government has created a monopoly here, churning out profit alone from the sector. We must gradually move away from this and ensure that fuel is purchased through open competition, and that its price is set in accordance with global market rates.

Bangladesh faces another weakness: a lack of adequate fuel storage depots, compounded by insufficient investment to expand their number. The country’s refining capacity is limited to just the Eastern Refinery. We must expand these refineries and increase their capacity. Doing so would allow us to purchase and store larger quantities of fuel when global market prices drop, a strategy successfully employed by countries like Singapore.

To increase the number of depots, Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) and foreign investment should be leveraged. Investment in the energy sector is crucial because it directly influences economic growth, job creation, and inflation.

For a long time, there has been a lack of new gas field exploration. We haven’t undertaken deep drilling operations and have failed to attract sufficient foreign investment for second-layer deep drilling.

Currently, the gas pipeline between Myanmar and India allows both countries to extract gas. Bangladesh also has a high probability of being able to extract gas from this same area. State initiative is necessary.

The influence of global politics is also noticeable here; if we import fuel cheaply from Russia, we may face resistance from the United States. While subsidies might be considered due to high fuel prices, they will not be beneficial for the state in the long run.

A prudent policy plan should be formulated by balancing import trade and the subsidy system. We must also explore the possibility of obtaining a Cash Incentive from the US. Nevertheless, being able to import fuel from Russia would ultimately be beneficial for us.

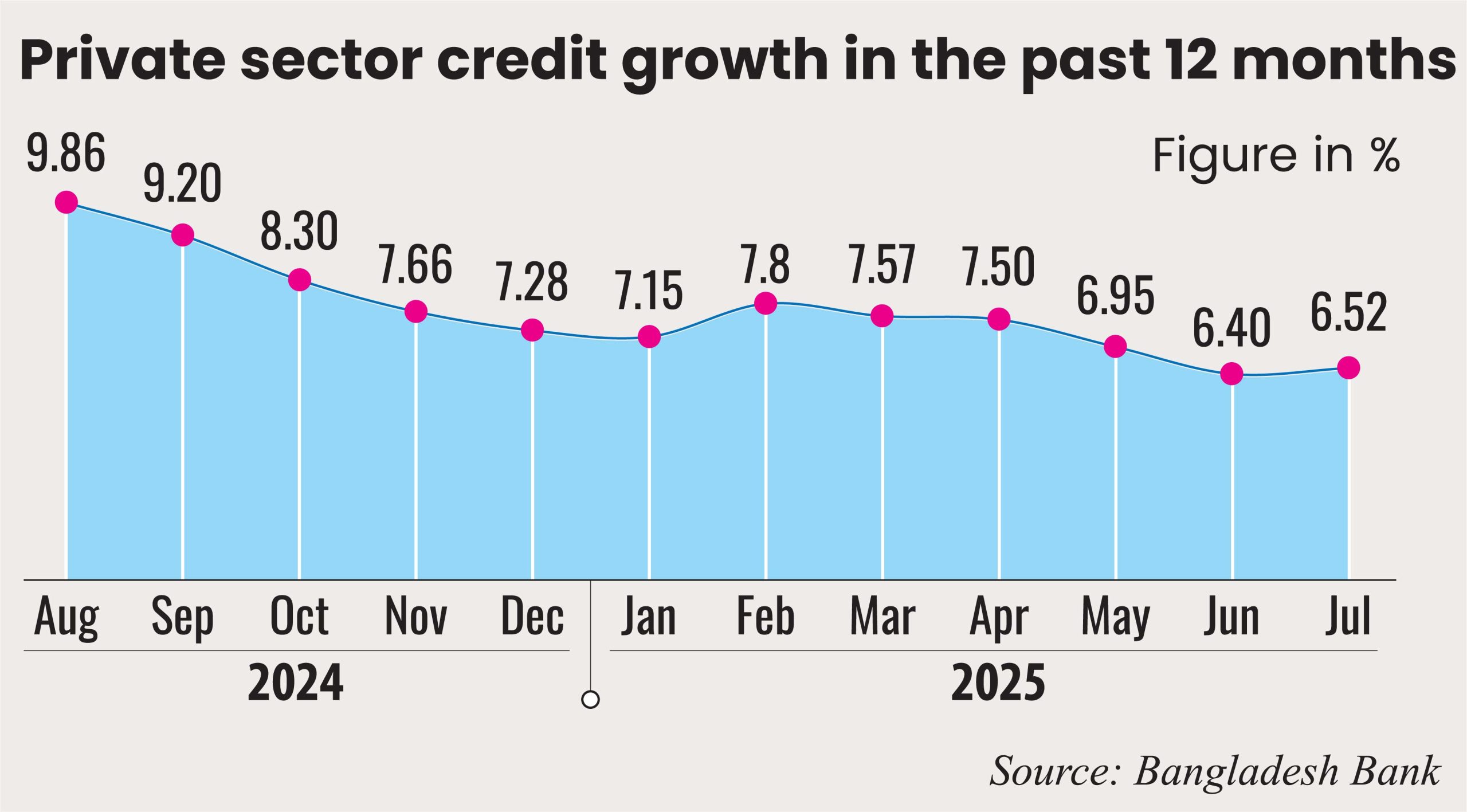

Now to the banks. High NPLs, liquidity shortages, and flawed governance issues have plagued the sector. Private sector credit growth has been falling freely for consecutive fiscal years. Do you suggest any immediate action or policy reform to restore confidence in the sector? When can we expect credit growth to go upward?

To expand industries, energy security must be ensured first. The current lack of energy security prevents our existing industries from producing at full capacity. Where industrial expansion isn’t even possible, it’s unrealistic to expect new investment.

Secondly, businesses have long enjoyed an interest rate of 9-6%. Now that the rate has reached 18%, business costs will naturally increase. The current policy rate is 10-16%. Consequently, a businessperson must borrow at a 16% interest rate, and if they hope to turn a profit, they will have to increase the price of their products to cover this additional cost. High domestic interest rates lead to higher costs of doing business, which in turn fuels higher inflation. However, the government has indicated that the policy rate will be reduced in the following monetary statement.

Another reason for credit contraction stems from a political climate in Bangladesh where banks were essentially plundered and used as tools for loot. According to the current government, there was previous under-reporting, which is now being corrected by adhering to international rules. This correction means that the amount of defaulted loans, previously stated as BDT 1500 billion, will now reach BDT 6500 billion. This sheer volume of defaulted loans is precisely why investment has vanished.

Our national wealth has been invested abroad – in the US, Turkey, Malaysia, and Singapore, instead of domestically. We must move away from the culture of plunder that has developed, where people believe that money taken from a bank does not need to be repaid.

Exposing defaulters to the media and demanding accountability might discourage the mindset of default among the business community. This elite exploitative circle is colluding with economic institutions and other businesspeople to plunder the entire state, which is the primary reason why the level of investment is not increasing.

Bangladesh Bank has injected billions of taka into the troubled banks to save them. A BDT 200 billion overhaul plan is currently being prepared. Will these efforts bring positive results?

My personal opinion is that Bangladesh has too many banks relative to the size of its economy. This number, along with the high number of Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFIs), should be reduced through a defined process.

The current idea of merging banks and NBFIs must be handled carefully. Simply merging ‘good’ and ‘bad’ banks without addressing the existing non-performing loans (NPLs) means we are just creating a new opportunity for default. The strategy for weaker and stronger banks should follow a specific process. The state needs to decide which banks are necessary to ensure inclusive banking for all citizens.

First, we need specific specialized banks for economic activities, and the necessity of the current ones should be reviewed. For instance, the functions of the Rajshahi Krishi Unnayan Bank and Krishi Bank overlap, as both are state-owned institutions focused on agriculture. If the Agriculture Bank has branches in Rajshahi, the regional bank shouldn’t be necessary. The primary goal of the Agriculture Bank should be to handle all agriculture-related loans nationwide.

Private banks should be assigned to cater separately to small, medium, and large industries. Based on these conditions, the central bank should reorganize the system while ensuring that depositors are not harmed and that there is no risk of default when customers try to withdraw their money.

Banks like First Security Islami Bank, with 90% non-performing loans, are now facing an existential threat. It’s impossible to save such institutions merely by injecting cash. The focus must instead shift to determining how the looting occurred, where the money and assets are, and how to lock down the funds if they were transferred abroad.

In my view, this cycle of NPLs cannot be stopped without exemplary punishment. As a citizen of the country, I want to see loan defaulters penalized and punished. Without any severe and deterrent measures, merely merging banks will not change the reality of defaulted loans.

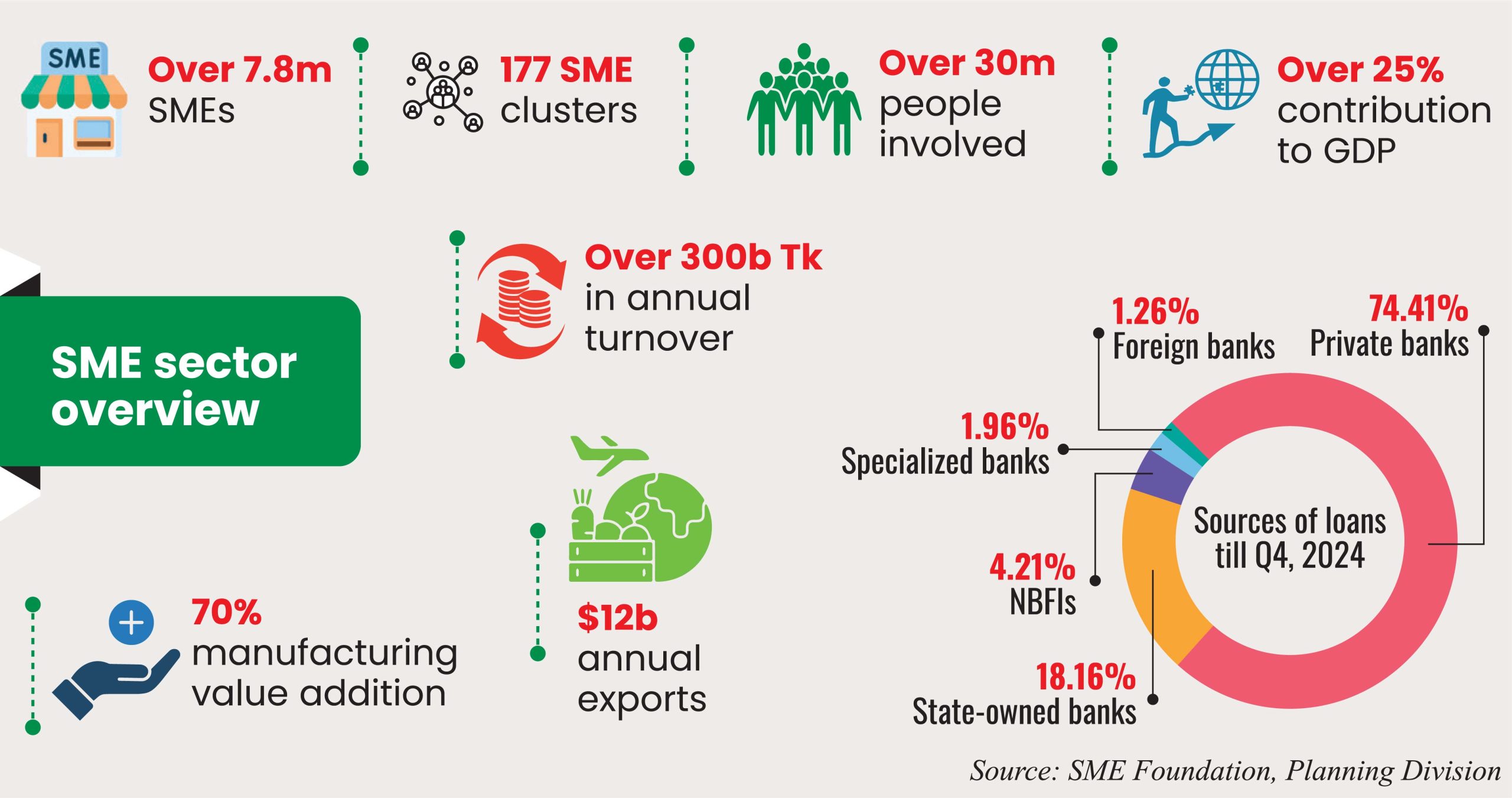

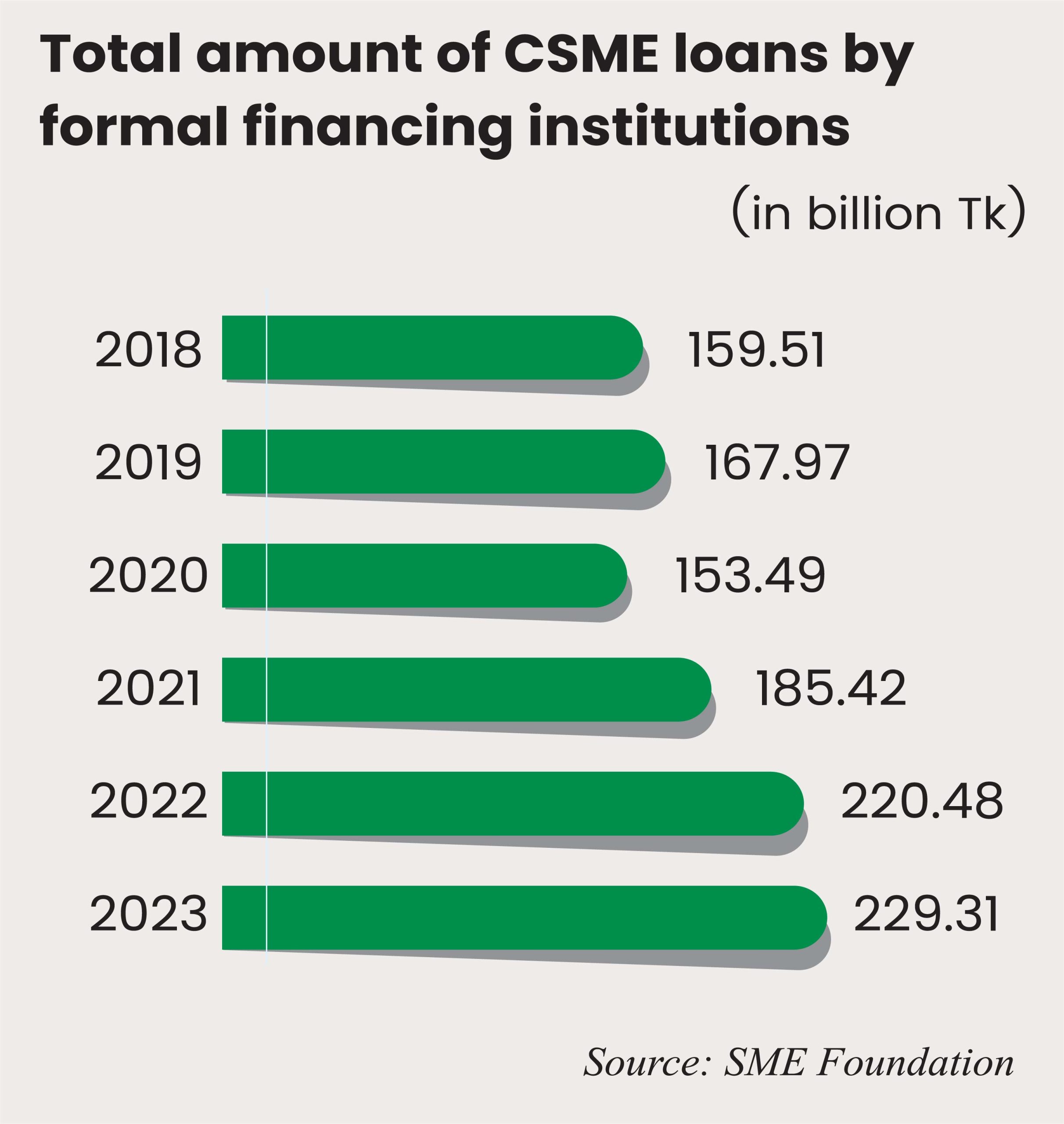

A fixed policy rate regime, i.e., 9% and 6%, has adversely affected the businesses, especially the SMEs and MSMES. Although the central bank has adopted a market-determined policy rate regime, it feels a bit too late. We have observed that large firms and borrowers have benefited from the facilities provided under government stimulus packages, whereas CMSMEs have been deprived. According to the BB data, borrowers under the cottage and SME categories received only 5.52 per cent of total disbursed loans and advances during January-March 2025.

Now, what can the Bangladesh Bank do for CSMES to heal? Should it introduce targeted refinancing schemes, or are deeper structural reforms needed?

For developing nations, the MSME (Micro, Small, and Medium-sized Enterprises) sector is vital, and the interrelationship between small, medium, and large industries is crucial for achieving developed-nation status.

In Bangladesh, MSMEs face two major hurdles: high utility costs and a risk-averse tendency in lending. MSMEs are charged higher electricity rates compared to large industries, which actively discourages investment in the sector. Banks also view SMEs as risky ventures, giving preferential treatment to medium and large enterprises during the loan application process.

If the state fails to nurture these smaller ventures, it will be impossible for them to grow into medium and large enterprises.

To properly nurture MSMEs and cottage industries, the first step must be to bring all of them under a proper registration system. Once registered, concessional loan packages, similar to those offered during the post-COVID period, can be introduced at favorable interest rates.

The distribution of the COVID-era stimulus packages had significant flaws. During the pandemic, when SMEs were struggling for survival, there was no time to verify registration status.

In a disaster, the most heavily affected should be rescued first. However, the Bangladesh Bank primarily aided institutions that were already registered. Another condition excluded businesses that had no prior bank-to-client relationship, meaning many small entities that had never taken a loan did not receive the stimulus. As a result, despite being the hardest hit, many MSMEs did not receive adequate government support.

While Bangladesh may meet all the conditions for LDC Graduation in 2026, the country lacks a comprehensive plan to achieve the necessary formalization of its economy. Roughly 60% of Bangladesh’s economy is informal. It is therefore uncertain whether Bangladesh can truly meet its developmental goals.

This circles back to registration. The state must create a roadmap outlining which parts of the economy will be formalized and which will remain informal. We can provide targeted incentives to small, medium, and large businesses separately when they are within a registration framework. Without this structure, providing the necessary support to these different segments is simply not possible.

The forex reserve is improving due to increased inflows of remittances and export growth. As the difference between bank rates and kerb rates has narrowed, informal transactions have decreased as well. What strategies can be implemented to sustain this balance?

The stability of a nation’s currency is a key indicator of both its economic and financial sector stability. The relative stability achieved in Bangladesh’s foreign exchange market over the last decade was encouraging (until the increasing reserve fell swiftly). Imports surged to an average of $89–90 billion around the Fiscal Year 2021-22 following the COVID-19 pandemic. Recognizing the looming crisis, where import growth significantly outpaced export growth, the government imposed import restrictions. This measure successfully brought the current import bill down to $58–60 billion.

However, the 25-29% reduction in imports of raw materials, intermediate goods, and machinery is now posing a threat to future economic growth. Given the current positive Balance of Payments (BoP) position, the government is considering gradually easing import restrictions. Maintaining export growth under these conditions would be beneficial for the taka’s value.

A critical question arises regarding the exchange rate management. The market was supposed to determine the taka’s value, but the central bank has been intervening by buying dollars to stabilize the rate. If the rate is allowed to increase later, will the BB sell dollars? More immediately, if the taka’s value were allowed to appreciate now (strengthen), although it would reduce remittance and export earnings, displeasing recipients and exporters, it would also significantly reduce import costs.

Since most production inputs and intermediate goods are imported, lower import costs would directly translate into lower prices for final goods. This is vital for managing inflation. While the inflation rate had declined for three consecutive months, it has recently risen again, which is typical during this season due to the seasonal price hike of essential commodities like chili and onions. This upward price pressure would be much easier to tackle if import costs could be lowered.

My personal view is that a gradual appreciation (lowering the price) of the dollar would actually lead to increased imports. Given that Bangladesh is largely an import-dependent exporter (for example, importing raw material for shirts before exporting the finished product), higher imports would support the export cycle. Even if this only adds a small amount of domestic value addition, it would still be collectively beneficial for the country’s economy.

Beyond macroeconomic factors, issues such as law and order, political instability, and weak investor confidence continue to undermine the investment climate. What steps should be prioritized to improve the overall business environment in Bangladesh? Any model country to follow to increase FDI inflow?

Historically, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Bangladesh has remained low. Data clearly shows that FDI inflows are minimal each year. The contrast with a peer like Vietnam is stark: Vietnam’s rapid ascent, becoming a key market for the US, is largely due to the massive FDI it has attracted over the last decade.

Bangladeshi industries now face an imminent crisis. As orders shift to Bangladesh, we lack the necessary technology to produce goods that meet higher design and quality standards.

For instance, India manufactures premium-quality t-shirts, unlike the lower quality often produced here. The advanced technology required for high-quality production demands investment. Unfortunately, accessing bank loans for this investment is difficult, as many banks are struggling with their own solvency. Even if demand for apparel increases, banks are unlikely to lend; it’s questionable whether the non-defaulting banks can distribute funds effectively after accounting for the 15 or so severely affected ones.

The state itself has created massive hurdles for banks by borrowing excessively each year. The business environment is severely damaged by loan defaulters. The money that was looted from our banks is now invested abroad, instead of domestically, where it could have at least fueled growth.

Foreign investors assess a country based on its political stability. They look beyond the immediate transition period, carefully considering who will control the country in the future. At a recent BIDA investment conference, investor focus quickly shifted from project concerns to the date of the next election. This highlights the election’s importance. Investors will weigh the risk of conflict, considering all factors before committing capital.

Therefore, simply holding an election with two or three participating parties is not enough to guarantee stability. Only if the election is globally accepted and a government is formed through an inclusive electoral process will foreign investor confidence return.

Alongside political stability, we must solve critical structural issues to attract foreign investors. We need to ensure a reliable supply of power and gas. Overcoming challenges in transportation, logistics, and the efficient release of goods from ports is imperative.

This will pave the way for a significant opportunity for private investment beyond just the RMG sector. Global tariff-related market contractions for countries like India and China won’t affect only the RMG industry; other industries will also face shifting markets. How well Bangladesh capitalizes on this depends entirely on the government’s competence and prudence.

It would be a significant achievement for Bangladesh if political parties could resolve internal conflicts and move away from the culture of disruptive, harmful politics, such as blocking roads.

A major success for the interim setup would be holding a genuinely fair election. If, despite having the opportunity to vote spontaneously, one-third of the population abstains, it will be a profound failure.

The financial sector will need healing. We may uncover more money laundering in the future. The roadmap the government leaves to address this massive damage will determine whether foreign investors can regain trust in our financial institutions.

Ensuring the flow of sufficient energy, power, and gas. If the government cannot manage this alone, a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model should be adopted.

Leveraging PPP for large infrastructure projects ensures efficient use of funds, relieves the pressure on the government to rely on tax revenue and borrowing, and allows both public and private entities to operate profitably. People are willing to pay for better services, but the platform for delivery is often missing; therefore, if the government cannot initiate projects, the PPP model should be actively used to implement necessary arrangements.

Most Read

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

A nation in decline

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

Does a tourism ban work?

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

You May Also Like