Protection without productivity gains risks isolation

BY Insider Desk

February 11, 2026

Across the globe, ‘trade protectionism’ has moved from the fringes of political rhetoric to the center of national policy. Major economies are deploying tariffs, subsidies, and restrictive measures to shield domestic industries. To discuss these pressing matters, Industry Insider turns to the expertise of Dr. Selim Raihan, a leading authority on international trade and a pioneer in economic modeling.

Dr. Selim Raihan is a distinguished economist and a Professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Dhaka. He is the Executive Director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM) and sits on the Board of Directors for the Global Development Network (GDN).

How does rising global protectionism change export-dependent economies? Can domestic demand shield Bangladesh?

Rising global protectionism reshapes the risk profile of export-dependent economies by making external demand more volatile, politically contingent, and, above all, less predictable.

For Bangladesh, whose growth model has long relied on preferential market access and cost competitiveness in the ready-made garments sector, this shift is unsettling. Higher tariffs, tighter rules of origin, labour- and climate-linked trade measures, and the broader reconfiguration of supply chains toward near-shoring all chip away at advantages that once seemed relatively secure.

Put simply, as advanced economies turn inward and prioritize strategic autonomy, Bangladesh faces a double challenge: defending market access while upgrading faster than before. From this perspective, protectionism turns exports from a stable growth engine into a source of macroeconomic vulnerability, exposing employment, foreign exchange earnings, and fiscal balances to sharper shocks.

Domestic demand can soften these blows, but it cannot fully replace exports, at least not in the near term. Bangladesh’s large population, rapid urbanization, and expanding middle class do provide a base for demand-led growth. Yet structural constraints remain binding.

Low real wages, widespread informality, limited consumer credit, and tight fiscal space restrict how far internal consumption can realistically go. What this implies is that export slowdowns do not just hit factories; they also feed back into domestic demand, especially given the RMG sector’s central role in employment and income generation.

Over time, policies that raise productivity, expand social protection, and support non-RMG sectors can deepen the domestic market. Still, domestic demand should be seen less as a substitute for exports and more as a stabilizer.

How vulnerable are Bangladesh’s exports to new tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff barriers?

Bangladesh’s exports are highly vulnerable to new tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff barriers because of their narrow concentration, limited market diversification, and dependence on preferential trade regimes.

The dominance of ready-made garments means that even modest policy changes in major markets such as the EU or the United States can have outsized effects on overall export performance. As Bangladesh approaches and moves beyond LDC status, the gradual erosion of duty-free, quota-free access raises exposure to tariffs. What once acted as a cushion against global competition is slowly disappearing.

At the same time, safeguard measures or informal quotas driven by political pressures in importing countries can quickly constrain market access for low-cost suppliers like Bangladesh.

Non-tariff barriers such as stricter labor standards, environmental requirements, carbon border measures, and complex rules of origin all raise compliance costs. These burdens fall unevenly. Larger firms may adjust, but smaller and medium-sized suppliers risk being squeezed out of global value chains altogether.

Global trade is becoming less about price alone and more about regulatory alignment. Therefore, Bangladesh’s export resilience will hinge on how quickly it can strengthen institutions, diversify markets and products, and align domestic regulations with evolving global norms.

Which protectionist measures are most common (tariffs, quotas, rules of origin)? Do they raise local consumption or raise costs?

Tariffs and non-tariff measures, especially rules of origin, technical standards, and regulatory requirements, are more common than explicit quotas, which are largely constrained by WTO rules.

Tariffs themselves have become more targeted and strategic. It is often aimed at specific sectors or countries rather than applied uniformly. Rules of origin have gained prominence in preferential trade agreements and regional blocs, becoming increasingly restrictive as governments seek to ensure benefits accrue to domestic or regional producers. Sustainability standards and labor and environmental regulations also function as de facto trade barriers by raising compliance thresholds, particularly for exporters from developing countries. These measures rarely boost local consumption in a lasting way. Instead, they tend to raise costs across the economy.

Protection may temporarily shield domestic producers or preserve jobs in politically sensitive sectors, but the broader effects are often inflationary and efficiency-reducing. Over time, higher costs are passed on to households and downstream industries, weakening purchasing power rather than strengthening it. This implies that modern protectionism is less about stimulating domestic demand and more about redistributing rents.

What additional pressures will Bangladesh face after LDC graduation when preferential market access declines?

Bangladesh will face intensified competitive and financial pressures as preferential market access, especially duty-free, quota-free access to major markets like the EU, gradually fades. The reintroduction of tariffs will squeeze margins in price-sensitive sectors such as ready-made garments, where competition is driven more by cost than by branding or technological sophistication.

Exporters will also face stricter rules of origin under standard trade regimes, making it harder to qualify for preferences without stronger backward linkages. At the same time, expectations around labour rights, environmental standards, and traceability are rising, pushing up fixed costs just as the tariff cushion disappears.

LDC graduation will also tighten macroeconomic and institutional constraints. Bangladesh will lose access to certain concessional financing and special and differential treatment, while being expected to align more closely with global regulatory norms.

Without faster diversification into higher-value products and new markets, export growth may slow. It will affect employment and the stability of the foreign exchange market. So the challenge will shift from gaining access to competing effectively, demanding stronger institutions, higher productivity, and a more resilient export structure.

Is it feasible for Bangladesh to pursue a dual strategy of expanding exports while also growing the domestic market?

It is feasible, but only with careful sequencing and deep structural reforms. Exports will remain indispensable for foreign exchange earnings, employment creation, and scale economies, especially in manufacturing. Domestic demand, in turn, can act as a stabilising force during external shocks. The two are not inherently opposed.

Export-led growth raises incomes and productivity, which then feed into consumption and investment at home. The problem lies elsewhere. Bangladesh’s current model is constrained by low wage growth, limited access to finance, and high informality. This weakens the link between export success and broad-based domestic demand.

For this dual strategy to work, domestic market expansion must be productivity-led rather than driven by unsustainable credit or fiscal stimulus. This means strengthening small and medium enterprises, improving infrastructure and logistics, deepening financial inclusion, and investing in skills so domestic firms can serve both local and export markets.

At the same time, diversifying exports beyond garments into light engineering, agro-processing, pharmaceuticals, and services can reduce vulnerability and strengthen domestic linkages. If incentives across trade, industrial, and social policies are aligned, the country can build a more balanced growth model.

What lessons can Bangladesh learn from Vietnam, India, or Indonesia about protectionism?

Vietnam has a deeper engagement with global markets rather than retreat. The country has signed high-standard trade agreements and aligned domestic regulations with global norms.

Vietnam has turned protectionist pressures into incentives for upgrading and investment. They paired openness with institutional reform and strategic state support to reduce vulnerability in a fragmented global economy.

India and Indonesia illustrate both the appeal and the limits of selective protectionism. India’s reliance on tariffs and localization has supported some domestic industries, but it has also raised input costs and weakened export competitiveness. Indonesia’s resource nationalism and non-tariff barriers have encouraged domestic processing in certain sectors. However, policy uncertainty has discouraged investment at times.

The lesson is clear. Protection should not be an end in itself. Temporary, targeted support for upgrading must be paired with export orientation, regulatory predictability, and openness to competition. Protection without productivity gains risks isolation, just as global trade becomes more demanding.

Which sectors among RMG, leather, agricultural products, light engineering, and pharmaceuticals are likely to be most affected?

RMG, given its dominance in Bangladesh’s export basket, and its reliance on preferential access. Even small tariff increases or tighter rules of origin can erode competitiveness. Rising non-tariff barriers, labor compliance, sustainability standards, and traceability add further pressure, especially for smaller factories. Leather and leather goods are also highly exposed due to persistent environmental compliance issues.

Agricultural products, light engineering, and pharmaceuticals face a more mixed picture. Agricultural exports are vulnerable to sanitary and phytosanitary measures and climate-linked regulations, which can restrict access even in the absence of tariffs.

Light engineering, though still nascent, is sensitive to scale constraints and rules of origin, but holds promise if regional value chains deepen.

Pharmaceuticals are relatively more resilient. The sector has stronger capabilities and domestic demand, though post-LDC graduation will tighten intellectual property and regulatory conditions.

What short-term and medium-term measures can the government take to cushion the impact of rising global protectionism?

In the short term, risk management and continuity should be the priority. This includes negotiating transitional trade arrangements after LDC graduation, actively pursuing bilateral and regional trade agreements, and preserving market access where possible.

Exchange rate flexibility, targeted export incentives, and temporary support for compliance costs, especially in labor, environmental, and certification areas, can help firms absorb sudden shocks. Improvements in trade facilitation, faster customs clearance, and digitalization can also lower non-policy trade costs.

Over the medium term, the emphasis must shift from cushioning to restructuring. Export diversification, skills upgrading, and deeper backward linkages can reduce dependence on vulnerable markets. Strategic investment in infrastructure, energy reliability, and ports will lower economy-wide costs. Equally important is strengthening institutions. We need standards bodies, regulators, and dispute resolution systems. The goal should not just be to survive protectionism but to adapt the growth model itself toward productivity and resilience.

If global protectionism intensifies over the next 5–10 years, what should Bangladesh’s growth model look like?

Exports will remain central, but their role must evolve from volume-led expansion in low-cost manufacturing to value-led growth. This growth has to be compliant. Emphasis on services, skills, and technology adoption is a must.

At the same time, domestic demand should emerge as a stronger secondary pillar. The pillar’s strength must come from rising real income, not fed by credit. This requires sustained productivity gains, better urban infrastructure, financial inclusion, and stronger social protection.

Public investment and regulatory reforms should crowd in private investment across both tradable and non-tradable sectors. In a more protectionist world, Bangladesh’s success will depend on combining outward orientation with internal strength. Bangladesh will remain open where it matters, aggressively build domestic capabilities, and ensure that growth is not only exportable but also inclusive and shock-absorbent.

Most Read

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

BY Sudipto Roy

August 08, 2025

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

A nation in decline

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

Environmental disclosure reshaping business norms

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

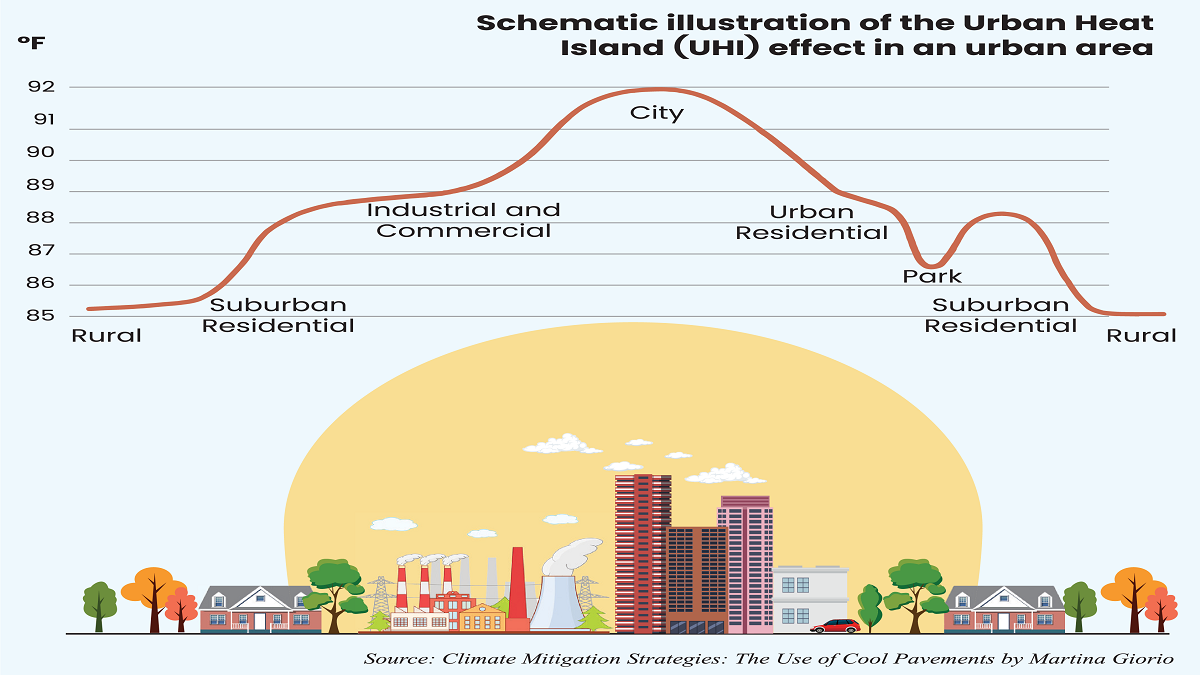

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

Does a tourism ban work?

You May Also Like