Who pays what for energy

November 22, 2025

The global conversation around energy is no longer about whether renewable power can compete with fossil fuels. Instead, the real debate is how quickly solar, wind, and storage can replace coal, gas, and even nuclear in different parts of the world.

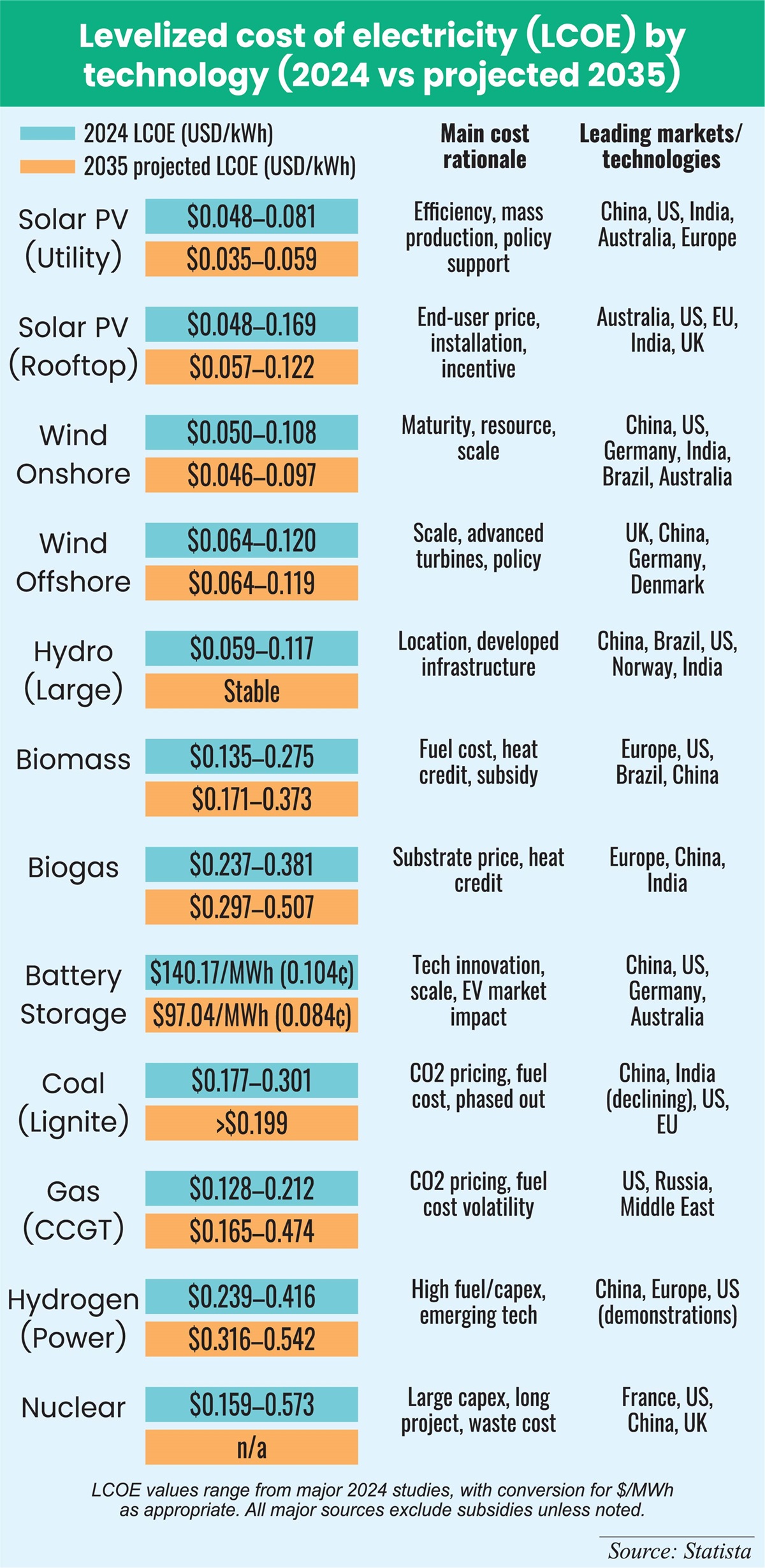

By 2024, the data had already made the case clear: utility-scale solar and onshore wind offer some of the lowest-cost electricity available anywhere, often, well under $4.68–7.02 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh).

Projected costs by 2035 suggest further declines, with solar PV expected at $3.51–5.85 cents/kWh and onshore wind hovering around $4.56–9.71 cents/kWh. Fossil fuels, meanwhile, are moving in the opposite direction, with combined-cycle gas turbines projected to reach as high as $47.38 cents/kWh due to fuel volatility and carbon pricing.

The question now is not whether green energy is affordable, but where, why, and under what conditions it emerges as the cheapest option. Let’s look at the cost profiles of some key green technologies:

Solar Photovoltaic (PV): Utility vs Rooftop

Utility solar remains the global frontrunner in low-cost generation. In 2024, the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for utility-scale PV stood between $4.80 and $8.07 cents/kWh.

By 2035, analysts expect further drops to $3.51–5.85 cents. The main reasons are mass production (China dominates this space), along with favorable policy measures like feed-in tariffs and tax incentives.

Rooftop solar is more varied; costs in 2024 ranged between $4.80 and $16.85 cents/kWh, projected to fall slightly to $5.73–12.17 cents by 2035. Markets with high retail electricity prices, such as Australia and parts of Europe, make rooftop solar highly competitive despite higher upfront costs.

Wind power: Onshore and Offshore

Onshore wind rivals solar PV in affordability. In 2024, its LCOE ranged from $5.03–10.76 cents/kWh, falling to $4.56–9.71 cents by 2035. Nations like China, Brazil, Germany, and the US lead in scaling wind, with turbine technology pushing efficiency higher every year.

Offshore wind still costs more, $6.43–12.05 cents/kWh in 2024, only nudging down slightly to $6.43–11.93 cents by 2035. But in countries with strong policy support, like the UK, Denmark, and Germany, large turbines and competitive auctions are pulling prices closer to land-based wind.

Hydroelectric power

Hydro has a unique profile; it generally sits between $5.85 and $11.70 cents/kWh, depending heavily on geography and existing infrastructure. Norway, Brazil, and China rely on hydro as a backbone, where sunk capital costs and reliable generation make it extremely stable. Yet, environmental and displacement concerns now weigh more heavily in project assessments.

Biomass and biogas

Biomass costs remain relatively high. In 2024, biomass LCOE was $13.45–27.49 cents/kWh, projected to rise further to $17.08–37.32 cents by 2035. Biogas follows the same trend, moving from $23.63–38.02 cents in 2024 to $29.72–50.66 cents/kWh by 2035.

Feedstock costs and limited scalability explain why these options are less competitive than wind or solar, though they retain niche roles in regions with cheap organic waste.

Battery storage

Battery costs are declining at an impressive pace. In 2024, storage averaged $103.59 per megawatt-hour (MWh), about 0.09 cents/kWh. By 2035, this could fall to $71.72/MWh, or 0.06 cents/kWh. The link between electric vehicles and stationary storage is crucial here; overcapacity in battery manufacturing is making storage cheaper and easier to scale.

Fossil fuels and nuclear

Coal (lignite) remains costly at $17.67–30.07 cents/kWh in 2024, with projections above $19.89 cents by 2035 as carbon pricing bites. Gas-fired CCGT (combined cycle gas turbine) plants had costs of $12.75–21.18 cents/kWh in 2024, but projections stretch to $16.50–47.38 cents/kWh by 2035, clearly showing the sector’s exposure to volatile fuel prices.

Nuclear, meanwhile, is consistently expensive: $15.91–57.33 cents/kWh, largely due to high capital costs, long construction periods, and waste management.

Hydrogen power is in an early phase, with LCOEs of $23.87–$41.65 cents in 2024, rising to $31.59–54.17 cents by 2035. Unless production and storage costs fall, hydrogen will remain a supplementary, not primary, source.

Country-wise price comparison

China offers perhaps the most striking numbers. In 2024, industrial power rates averaged $0.09/kWh, while new renewable projects came in cheaper than coal or gas. Large-scale policy tools, such as green certificates and mandatory renewable integration, explain the country’s dominance.

India’s solar PV costs are among the lowest globally, at around 4 cents/kWh. Auctions in recent years saw solar plus storage bids dip to ≈$3.73–4.19 cents/kWh, already below coal or nuclear.

The US presents a wide range: solar PV at $31.59–$99.45/MWh, onshore wind at $29.25–$78.39/MWh, and CCGT gas at $47.97–$115.83/MWh. Battery storage paired with solar costs $40.95–$225.81/MWh. Despite variation across states, federal and state incentives make solar and wind competitive nearly everywhere.

Australia, on the other hand, combines high retail electricity prices ($0.29/kWh in 2025) with some of the cheapest renewable generation. Solar and wind LCOEs sit at $0.03–$0.05/kWh, helping explain why rooftop solar dominates households and businesses. Policy initiatives, such as the Cheaper Home Batteries Program, further enhance adoption.

Across Germany, France, Spain, and the UK, solar and wind LCOEs range from $3.51-10.53 cents/kWh. By contrast, retail grid prices are far higher, between $0.33 and $0.46 cents/kWh, particularly in Germany, Italy, and Ireland.

In countries like Brazil, Norway, Canada, and Russia, hydroelectric power dominates thanks to geography and infrastructure. Costs remain at the stable $5.85–11.70 cents/kWh range, supporting both energy independence and export opportunities.

What explains the cost differences?

Renewable energy prices do not fall evenly across the globe, and the differences often come down to a mix of rules, resources, and readiness.

Policies such as feed-in tariffs, carbon pricing, or tax breaks can significantly impact project costs. Mature markets like China, the United States, or Europe benefit from deep supply chains that drive prices lower than in countries that rely heavily on imports.

Natural conditions also matter: more sunlight hours, steadier winds, or well-positioned rivers can shape the levelized cost of electricity.

Infrastructure adds another layer to the story. Nations with stronger grids and better storage systems can absorb renewable energy more cheaply, while weaker networks end up paying more to balance supply and demand.

On top of that, technology keeps reshaping the numbers. New solar cell designs, such as TOPCon and perovskite, push efficiency higher, while the rise of larger offshore wind turbines steadily drives costs downward.

Are green technologies expensive?

Calling renewables expensive no longer matches the evidence. By 2024, new solar and wind projects were cheaper than new coal or gas projects in nearly every market, sometimes even more affordable than running old fossil plants.

What remains costly are early-stage technologies like green hydrogen or next-generation storage. But for mainstream renewables, the cost rationale is firmly on the reasonable side.

Battery storage cost, projected to fall from $104/MWh in 2024 to $72 by 2035, is removing one of the last barriers to 100% renewable grids. Hydrogen and floating solar are experimental today, but could play larger roles within two decades.

Global investment flows confirm the shift: China’s Belt and Road now invests more in renewables than fossil fuel projects, and solar installations worldwide are projected to reach 655 GW this year, with double-digit growth continuing through 2030.

Global evidence leaves little doubt; renewables are not only viable, they are consistently the cheapest form of new electricity in most regions. Solar PV and onshore wind dominate on cost grounds, while storage is catching up quickly.

Hydropower remains critical where geography allows, and biomass fills smaller, specialized roles. Fossil fuels, once considered cheap, are increasingly undermined by fuel volatility and carbon pricing.

Hence, the ‘green premium’ that once defined renewable energy has all but vanished.

Syed Raiyan Amir is a Senior Research Associate at the KRF Center for Bangladesh and Global Affairs (CBGA). With a strong background in international affairs, he previously served as a research assistant at the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Republican Institute (IRI).

Most Read

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

A nation in decline

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

Does a tourism ban work?

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

You May Also Like