Why Bangladeshi companies fail despite having good audit reports?

February 09, 2026

Over the past several decades, numerous business organizations in Bangladesh have failed or fallen into severe financial distress. While some of these failures were linked to financial corruption or governance lapses, a significant number involved reputed and seemingly well-managed companies. Notably, many of these firms had no major reported irregularities and, in several cases, had received a good audit report shortly before their failure. So why did they fail?

When listed companies collapse, public scrutiny tends to focus quickly on auditors. Questions arise- were the audit reports incorrect, misleading, or negligent? Or does the real cause of business failure lie beyond the scope of what an external audit is designed to detect?

To find the answer, we must first clearly understand what an independent auditor’s report actually means and what it contains. Then we will review the main causes of business failure and examine how closely they relate to an independent auditor’s report.

Auditor’s report and financial statements

A common misconception about an independent auditor’s report is to treat the audit report and the financial statements as the same document. In reality, financial statements are prepared entirely by management. External auditors neither prepare them nor have the authority to modify them.

The role of the external auditor is limited to expressing an independent professional opinion, based on International Standards on Auditing (ISA), whether the financial statements prepared by management are presented in accordance with applicable accounting and financial reporting standards.

Another widespread misunderstanding is the tendency to reduce the entire audit report to one familiar sentence: “In our opinion, the financial statements present fairly…”

From this single line, many conclude that the company is strong, financially secure, and risk-free. In reality, an independent auditor’s report is not a certificate of financial strength, cash-flow stability, or long-term sustainability. It is simply a professional opinion on whether past-period financial statements comply with accounting and reporting standards.

Under ISA, auditors can never declare a financial statement to be 100% accurate or error-free (absolute assurance). They can only state that the financial statements are fairly presented (reasonable assurance).

What the auditor’s report can and cannot identify

According to the International Standards on Auditing (ISA), the auditor’s scope is designed to verify the integrity of financial reporting. Within this scope, an auditor can detect whether a company’s accounting has been performed in accordance with applicable standards and whether the chosen accounting policies have been applied consistently over time.

The report identifies significant errors or material misstatements and ensures that all necessary disclosures have been provided to the public. However, it is equally important to recognize that there are certain aspects of a business that an auditor’s report simply cannot detect.

The nuances of these reports range from owners and directors to investors, yet the technical language often obscures the critical signals hidden within. While an audit opinion may not explicitly forecast a company’s collapse or declare it corrupt, it provides essential clues about the entity’s financial health.

Standard and highlighted opinions

At the most favorable end of the spectrum is the Unqualified Opinion. This indicates that the financial statements align with accounting standards and all necessary compliance measures, making it the generally accepted standard for a reliable audit report.

In contrast, an Emphasis of Matter does not necessarily invalidate the report. It draws the reader’s attention to significant uncertainties, such as major ongoing lawsuits or concerns regarding the company’s ability to continue as a ‘going concern,’ ensuring these pivotal issues are not overlooked.

Modified opinions and limitations

When the auditor encounters significant departures from standards or restrictions, they issue a Modified Opinion. A Qualified Opinion indicates that, while the statements are mostly accurate, there is a specific red flag or exception the user must note. Far more serious is the Adverse Opinion, which acts as an explicit red alert; it warns that the financial statements are fundamentally misleading and should be considered unreliable.

In some cases, the auditor may issue a Disclaimer of Opinion when they are unable to form a conclusion because they were unable to conduct a proper audit. This is the result of a severe Limitation of Scope, meaning the auditor did not receive sufficient information or evidence required to do their job.

Profit and cash are not the same

Profit is an accounting result. Cash is the condition for survival. A financial statement generally consists of five components. Among them, the three most important are the Balance Sheet, the Income Statement (Profit & Loss Account), and the Cash Flow Statement. Users typically make the mistake of focusing heavily on the Income Statement, while the Cash Flow Statement receives far less importance. But to truly understand a company’s future, cash flow is more important.

An external auditor’s report cannot determine whether a company’s future cash flow will remain sustainable or whether the business possesses the resilience to withstand unforeseen financial pressures and crises.

In countries like Bangladesh, an unqualified audit opinion frequently generates a false sense of security. Boards, owners, and general users often assume a clean report implies total corporate health. However, an unqualified opinion merely confirms adherence to reporting standards; it does not confirm that the company is financially stable, possesses strong cash flow, or operates within a framework of controlled risk.

Issues with poor working capital management

The primary cause of business failure is often poor working capital management. As established, cash is the fundamental condition for a business to survive, and when financial discipline erodes, a collapse can begin silently.

Many businesses appear profitable on the income statement while simultaneously suffering actual cash losses. This discrepancy arises because corporate cash is often trapped on the balance sheet.

A company may report a healthy profit, yet it can still face a liquidity crisis if receivables from credit sales are not collected or if inventory levels rise excessively before being sold.

Liquidity is destroyed when VAT and advance taxes remain withheld by the government, or when advances and deposits continue to expand. In many cases, these long-term inefficiencies are dangerously masked by repeated short-term borrowing.

It is vital to remember that these critical issues are reflected in the balance sheet, not the income statement. Because these trends do not necessarily violate accounting standards or distort reported profit figures, they often escape the scrutiny of those who look only at the surface.

Excessive debt and leverage

Companies expand aggressively, over-leveraging and ignoring whether future cash flow can actually service the debt. Large payments due at maturity are overlooked, covenants are violated, and corrective action is delayed until it becomes meaningless. New loans are taken simply to repay old ones, which only delay collapse rather than prevent it.

Over time, rising interest costs consume operating profit, dependency on a single lender amplifies refinancing risk, and the absence of any deleveraging strategy ultimately turns debt into an inescapable trap. Debt servicing becomes unsustainable and leads to liquidity crisis, insolvency, and ultimately collapse.

Audit cannot identify cash flow crisis early

An external audit is conducted periodically, typically annually. Audit reports review past performance, not the future. Audit opinions are sample-based; they are never based on every single company record. Often, going-concern warnings appear only after lenders have already restricted credit exposure. Audit is not designed to detect early-stage liquidity crises.

Although cash flow failure is one of the primary reasons for corporate collapse, the roots of failure lie much deeper. In most organizations, collapse does not start with numbers; it starts with a leadership mindset, governance weaknesses, strategic mistakes, operational inefficiencies, reckless financing practices, and a culture that ignores risks rather than confronting them.

Corporate governance failure

Weak corporate governance does not immediately break a company; rather, it slowly destroys its immune system. Many local organizations operate with weak or non-existent boards that function only for compliance, while independent directors remain independent only in name.

There is no real segregation of power; ownership, board, and executive authority merge into one point, leaving mistakes unchallenged. Whistle-blower mechanisms are absent, so employees see risks but cannot raise concerns safely, while management override becomes normalized under the owner’s instruction.

Ultimately, a poor tone at the top shapes the organization, indiscipline becomes acceptable, early warning signals are ignored, and governance exists only on paper.

Compliance issues

Listed companies in Bangladesh are mandatorily subject to both financial audit and Corporate Governance (CG) compliance examination under the BSEC Corporate Governance Code. These CG audits verify the existence of prescribed structures, including board composition, audit committee, nomination and remuneration committee, and the appointment of key officers such as the CFO, Head of Internal Audit, and Company Secretary.

However, CG audit is fundamentally compliance-based. It confirms structure and documentation, not effectiveness. It does not assess whether boards genuinely challenge management, whether independent directors act independently, or whether finance and internal audit functions have real authority.

As a result, CG audit cannot guarantee good governance. A company may have an unqualified audit report and full CG compliance, yet still suffer weak oversight and suppressed risk reporting. Compliance ensures structure; governance demands behavior and accountability.

Vulnerability of privately owned companies

Privately owned companies face less regulatory scrutiny, no mandatory CG compliance, owner-dominated boards, and limited external challenge. As a result, cash flow stress and governance failure often remain hidden until liquidity collapses entirely.

In many privately owned Bangladeshi companies, owners themselves act as CEOs or appoint close family members or relatives to the role. Decisions, therefore, often rely on instinct, personal experience, and perception rather than data and structured analysis. Strategic risks go unchallenged.

Many organizations lack structured, formal HR policies. There is no planned succession system, nor performance-based accountability frameworks. As a result, organizations become person-dependent, inefficiencies grow, and financial leakage increases.

Without professional HR leadership, HR departments become mere administrative extensions of ownership. Operational weaknesses gradually transform into direct cash crises.

In many privately owned companies, CFOs are often excluded from strategic decision-making. Cash-flow warnings are frequently overshadowed by sales pressure, and finance is treated merely as a back-office support function, reducing the CFO’s role to reporting rather than leadership.

When the finance head lacks authority, financial discipline weakens, early warning signals remain unheard, and the organization gradually walks into a liquidity crisis.

One of the most crucial weaknesses in many local organizations is an ineffective or purely symbolic internal audit. In some companies, it exists only on paper; in others, it does not exist at all. Even when it exists, an internal audit often reports to management rather than the board. This is a cultural weakness characterized by overridden controls, ignored audit findings, weak documentation, missing SOPs, and unaddressed fraud risks.

Strategic and operational failures

When corporate governance becomes weak, its effects are not immediately visible, but collapse is inevitable. Day by day, systems break down, everything becomes dependent on people rather than processes, and organizations keep moving forward without real strength within.

In many companies, increasing sales at any cost is considered a badge of success. But in reality, aggressive sales policies often create the foundation for severe future financial collapse.

In the race to boost top-line revenue, organizations compromise normal business prudence, convert receivables into long-term dues, and erode margins through heavy discounts and incentives. Often, to meet year-end targets, goods are pushed into the market, only to later return or be written off as bad debts.

On the other hand, even flawless execution cannot save a business built on the wrong strategy. Expanding without proper feasibility analysis, entering unrelated industries for prestige, or over-diversifying beyond organizational capability are common mistakes.

The final collapse

As mentioned earlier, independent auditors review prior periods, verify that completed transactions were properly recorded in the books, and assess compliance with accounting and reporting standards. But the business failures we have discussed so far- leadership weakness, governance breakdown, working capital indiscipline, liquidity crisis, reckless borrowing, operational inefficiency, or strategic misjudgment- none of these falls within the responsibility of the external audit.

That is why corporate liquidity stress, governance collapse, internal control weakness, or impending business failure do not and cannot directly appear in the Independent Auditor’s Report, even when the audit opinion is unqualified or generally perceived as a ‘good’ audit report.

For any stakeholder who truly wants to understand whether a business is at risk of failure, relying solely on the independent auditor’s report is never enough. They must review and analyze the financial statements themselves. In this context, users of financial statements must keep the following audit opinion indicators in mind: a modified opinion, which indicates significant issues that are extremely dangerous to ignore; emphasis of matter, which are often serious warning signals; and a limitation of scope, which signals weak internal controls, governance failure, or management restrictions.

Ultimately, preventing or identifying business failure is not a matter of audit; it is a matter of governance. There is no alternative to practicing strong corporate governance.

Asif Md Tanvir Hossain FCA is the chief financial officer of KDS Group, a fellow member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Bangladesh, an executive member of ICAB Chattogram region, and a member of Chittagong Taxes Bar Association.

Most Read

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

BY Sudipto Roy

August 08, 2025

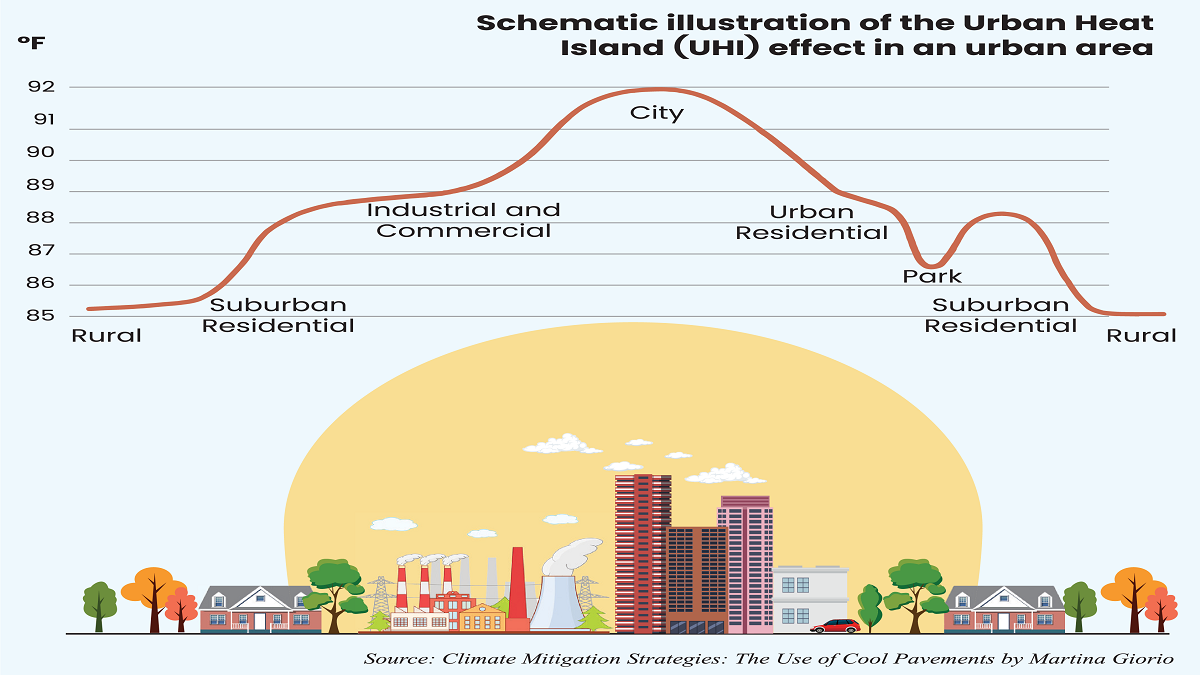

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

A nation in decline

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

Environmental disclosure reshaping business norms

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

Does a tourism ban work?

You May Also Like