Bangladesh’s preparedness for an AI transition

BY Md. Imran

February 09, 2026

An entry-level AI engineer in Dhaka typically starts their career earning approximately BDT 0.72-1 million per year ($5,800–$8,200). Across the ocean, their peers in Silicon Valley start at $115,000. For a more realistic comparison, a graduate in India commands nearly double the Bangladeshi rate in terms of purchasing power and base pay.

The salary gap is just one aspect of the industry. It has many things tagged along that beg to be questioned. It is the ‘canary in the coal mine’ for industrial readiness.

Does the nation have the human capital and infrastructure to transition from a labor-intensive economy to a data-driven one? Or will it remain a consumer of expensive foreign technology? Do we have enough job opportunities? Can we make a mark in the global market? What is the preparedness of Bangladesh in AI?

Market size

The global AI market is no longer a niche tech sector; it is a $850 billion powerhouse projected to exceed $3.6 trillion by 2034, according to the research firm Predance and DemandSage.

What about Bangladesh’s AI market? While the broader ICT market is valued at approximately $8.88 billion in 2025, the specific AI automation and services segment is currently in its nascent stage.

According to the 2025 National AI Readiness Assessment (RAM) report (launched by the ICT Division, UNESCO, and UNDP) and supplemental data from the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA), the AI-specific sector is small yet crucial. However, the ICT sector, the ‘parent’ of AI, is projected to reach $12.07 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of roughly 6.33%.

Global rank

To understand the preparedness gap, we must look at the numbers: market size, the volume of specialised graduates, and research output.

According to the RAM report, Bangladesh has built strong e-government foundations and enjoys high public trust in digital services. But the country has gaps in high-end computing and specialized skills compared to regional peers.

In the global AI hierarchy, a clear stratification has emerged, with the United States leading with a massive $470 billion market. In comparison, China is a scale powerhouse, with a $119 billion valuation.

In the South Asian region, India is the fastest-growing player in AI, with a $11.1 billion market expanding over 25% annually. India has one of the most significant government investment budgets supported by the IndiaAI mission, estimated at $1.24 billion.

This mission has already onboarded 38,000 GPUs available to startups at subsidized rates as low as ₹65 per hour ($0.71). Even though India is about 20 times larger than Bangladesh in terms of investments, startups, lab facilities, institutions, and curriculum, we still significantly lag in almost everything. Bangladesh’s closest competitors in this field are Vietnam, Pakistan, and Nigeria.

In 2026, Vietnam has established itself as the regional leader with a projected AI market size of $1.1 to $1.3 billion and a massive digital economy valued at $45 to $50 billion. In comparison, Bangladesh has a small market size of approximately $1.1 billion, and is focusing its efforts on Fintech and Agri-tech.

Graduates and research

The real engine of AI is talent. Here, the disparity becomes even more visible. Although the country produces a good number of ICT graduates every year, estimates go up to 25,000, the skill issue remains. Most graduates are absorbed into traditional software maintenance or web development; less than 5 per cent possess specialized training in deep learning, NLP (natural language processing), or big data architecture. The curriculum is often criticized for being outdated.

In India, the curriculum is rigorous, combining AI studies with traditional subjects such as Physics, Chemistry, and Electronics. They focus heavily on complex mathematics and practical applications. The result is evident in the number of Indians in company leadership and engineering roles at international AI brands.

The best example is the USA with a research and innovation model. Students explore cutting-edge fields such as neurotechnology and the ethics of AI. Their programmes are flexible, which combine AI with the arts or healthcare. Under the ‘Capstone Project,’ students work directly with giants like Google to solve real-world problems before they even graduate.

Bangladesh, on the other hand, focuses on building ‘Generalist’ engineers. While our students are strong in math and core coding, we lack specialized courses in AI leadership, edge computing (AI for small devices), and formal AI governance.

The same differences are seen in the field of research. In the last two years, according to Oxford Insights, China published nearly 60,000 AI research papers, matching the combined publications of the US, UK, and EU.

Our closest competitor, Vietnam, published more than 4,000 papers, double that of Bangladesh’s 2,000 academic publications recorded in 2021.

Regarding AI labs, India has launched 31, Vietnam has some 30 research centres, and Bangladesh has fewer than 10 dedicated university labs, primarily within BUET, DU, and NSU, many of which suffer from severe funding and hardware constraints.

Despite the gaps, Bangladesh is not a ‘zero-AI’ zone. The financial sector is the frontrunner in that scenario. bKash has integrated AI for automated KYC and fraud detection. Their work reported a 76 per cent productivity boost in agent onboarding. In logistics, startups like ShopUp use AI for route optimization, significantly cutting delivery times.

Even the traditional RMG sector is seeing movement; a few forward-thinking factories are using computer vision to detect fabric defects in real time.

According to research published in Preprints.org (2025), factories using AI-powered quality assurance (QA) systems achieved a 15-20 per cent decrease in product defects, saving millions in rejected export waste.

Is Bangladesh ready?

Infrastructure is the ‘refinery’ where raw data becomes economic value. Here, Bangladesh faces its steepest climb. AI requires high-performance computing (HPC), specifically GPUs.

We have limited high-end computing capacity, followed by ‘not up to the mark’ power supply outside the major cities. The safety of data and the thinness of guidelines on ethical use also limit the industry to certain areas, making AI a fun activity for the general public.

Although the Personal Data Protection Ordinance (PDPO) 2025 was recently adopted, its enforcement mechanisms are still in their early stages.

Countries that succeed, like Vietnam and Singapore, build robust university-industry pipelines. In Vietnam, the government has moved aggressively to allocate $1 billion to support AI initiatives and enhance infrastructure by the end of 2025.

In Bangladesh, the academic curriculum is often five to ten years behind industry needs. While platforms like Muktopaath offer promise, there is a desperate need for ‘Industrial Pilot Zones’ where students can work on real-world datasets provided by the private sector.

A significant, often overlooked hurdle is the digital divide. According to the UNESCO 2025 assessment, only 44.5 percent of the population uses the internet regularly. This creates a data bias: if AI models are trained only on data from the urban elite, the resulting services will fail the rural population, which is the backbone of the agricultural and manufacturing sectors.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS survey of July-September, 25-26) says ownership of smartphones is far higher in towns and cities: 80.8 percent of urban households have at least one device, compared with 68.8 percent in rural areas.

The ICT Access and Use Survey of 2025 says internet penetration in Urban Dhaka leads at 71.4-78 percent via broadband/5G connections, while rural regions average 36.5 percent. Districts like Madaripur’s penetration (~36 percent) and Kurigram’s (~33 percent) lag significantly, relying primarily on mobile data. These gaps need to be addressed and bridged with proper support from investments, training, and work.

There is a lack of sovereign AI development. Most local AI efforts currently rely on ‘API-calling’ foreign models like OpenAI’s GPT or Meta’s Llama. While useful, this places Bangladesh’s data and digital sovereignty in the hands of foreign corporations.

The Enhancement of Bangla Language in ICT (EBLICT) project is a strong start, but it requires massive scaling to create local large language models (LLMs) that understand the needs and nuances of the country’s people.

AI will reconfigure global competitiveness; lagging now means losing the ability to compete in the 2030s using outdated 2010s labor models.

To turn the tide, Bangladesh must move from being a mere consumer to a producer. UESCO has recommended a central AI governance office, subsidising GPU power for startups, and standardizing data-sharing across all industrial supply chains.

Bangladesh will thrive exponentially if it can adapt to the AI transition. However, countless limitations are present. It surely will be difficult, but not at all impossible.

Most Read

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

BY Sudipto Roy

August 08, 2025

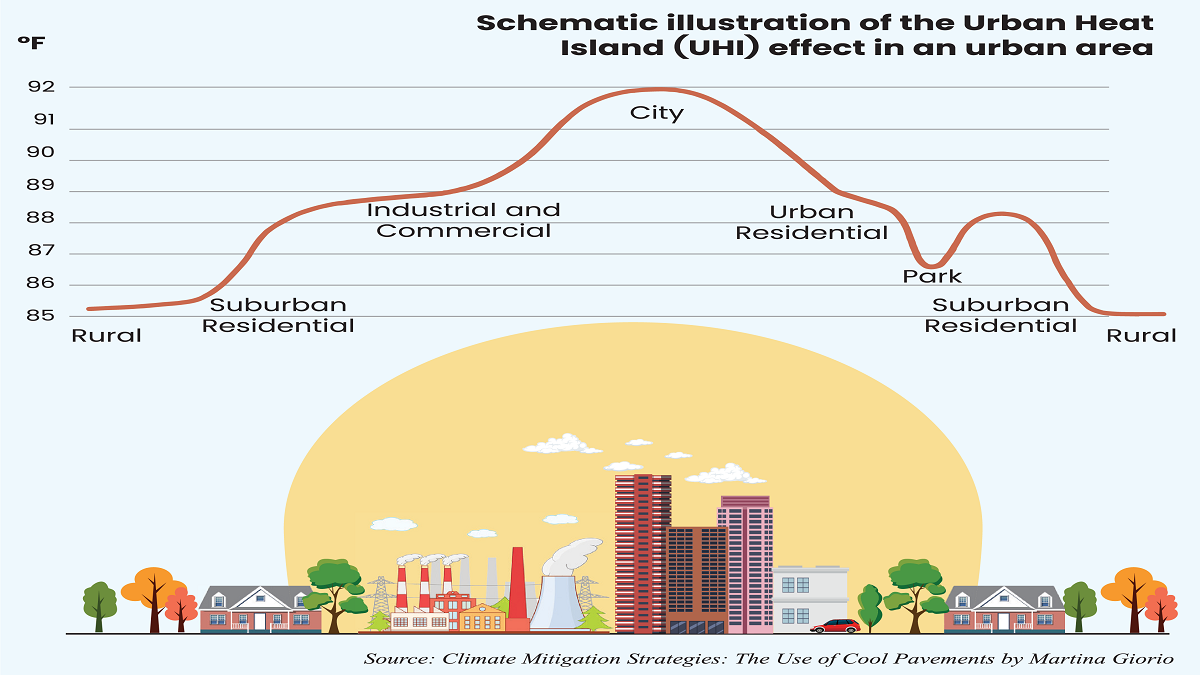

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

A nation in decline

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

Environmental disclosure reshaping business norms

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

Does a tourism ban work?

You May Also Like